Duane Eddy (Part One)

Rebel Rouser

Duane Eddy and The Rebels @ Jamie Records

by Hampton Jacobs

Duane Eddy and The Rebels @ Jamie Records

by Hampton Jacobs

Nowadays, it's extremely rare to tune in a contemporary Pop radio station and hear an instrumental hit. Today's Country, Rock and R & B/Hip Hop releases all feature vocals with instrumental accompaniment. Only stations that cater to fans of Adult-Contemporary music, Classical music and/or Jazz play instrumental recordings on a regular basis, and those formats represent a tiny segment of the commercial music industry. True, there are still a significant number of instrumentalists active in the music business, and some of them are quite successful (Yanni and André Rieu come to mind). However, they're hardly the norm, and the amount of airplay their records get is neglible.

Such was not always the case. Instrumentals have been a staple of popular song since the days of sheet music and pianos in the family parlor. The advent of the Swing Era in 1935, with featured band singers that commanded the public's attention, began the slow but gradual progression toward vocalist dominance. By the early 1950s, the big bands had almost died out, and vocal stars like Frank Sinatra, Dinah Shore, Patti Page, Doris Day, Teresa Brewer, Perry Como and Nat "King" Cole had taken over the hit parade. Rock 'n' Roll debuted in the mid-'50s as a vocal genre like none before it, with wild and uninhibited singing by Bill Haley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard and Elvis Presley setting the pace. However, the 1950s was a culturally conservative time in America. Back then, a lot of people considered Rock vocalists vulgar, coarse and severely lacking in musical training (which many were). In The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock 'n' Roll, historian Greg Shaw argues that conservative outrage over the perceived excesses of Rock singing opened the door for instrumental Rock 'n' Roll groups. "Undiluted Rockabilly (vocals) had little commercial appeal," he reminds us. What's more, by 1958, "the rockabilly style of singing was becoming dated, while the new teen ballad style depended on songs and productions crafted in the big studios of New York and Philadelphia." Record companies were signing up Rock balladeers by the dozen, while hundreds of would-be Elvises were left languishing on the vine. Rock bands faced a dilemma: Fronted by singers, they'd now be forced to play watered-down music they and most of their fans didn't care for. "These bands just wanted to rock," Shaw writes, "and they played for audiences that just wanted to drink and dance. (So) why not dispense with the singer altogether?"

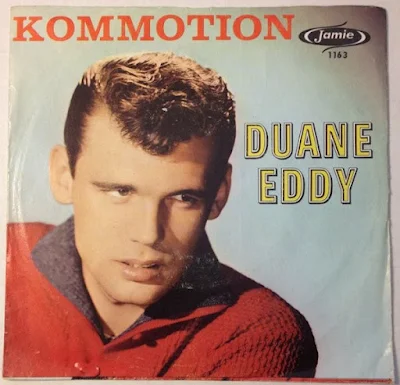

That's exactly what many regional bands did. A few big city studio musicians took notice of the trend, and soon, raw Rock devotees had their choice of instrumental hitmakers to choose from. The first was R & B keyboardist Bill Doggett, whose 1956 recording of "Honky Tonk" was Rock's first instrumental million-seller. In rapid succession came Dave "Baby" Cortez" playing his "Happy Organ," Link Wray itching for a "Rumble," Preston Epps hawking his "Bongo Rock," Sandy Nelson holding forth with his "Teen Beat," The Rock-A-Teens peddling their crazed "Woo-Hoo" rhythm, Santo and Johnny inducing people to "Sleep Walk" with bluesy steel guitar chords, Bill Justis and Ernie Freeman acting "Raunchy" on separate record labels, and The Champs throwing back shots of "Tequila" (not necessarily in that order). A shy, Country music-loving guitar prodigy from Phoenix, Arizona quicky rose to the top of the heap. His name was Duane Eddy.

Duane was actually born and raised in Corning, New York, but he and his family relocated to Arizona when he was thirteen. In Coolidge, Duane soaked in local Country music influences, becoming an ardent fan of Nashville guitar wizards like Hank Snow, Merle Travis and Chet Atkins. One of his favorite haunts was Country radio station KCKY. In those days when access to radio personnel wasn't as restricted as it is now, the boy was known to beg deejays for copies of old Country singles. One of the more accomodating jocks, Lee Hazlewood, later recalled: "I stole sufficient records from our files . . . for us to become fast friends." That friendship blossomed after Hazlewood, an aspiring record producer, learned of Duane's musical prowess.

Since the age of five, Duane had been fascinated by string instruments. He'd mastered acoustic guitar by his teens, and could also acquit himself capably on the banjo, the twelve-string bass, and the Hawaiian pedal steel guitar. In 1955, Hazlewood relocated to Phoenix, where he began producing record dates for local artists. Duane followed him there after graduating from high school, and began working as a session musician. One thing led to another, and Hazlewood found himself writing and producing Duane's first single, "Soda Fountain Girl", released in late 1956 or early '57. Ironically, it was a vocal record, a duet performance with Jimmy Delbridge that was billed as "Jimmy and Duane." Featuring instrumental accompaniment by a Country outfit called The Western Melody Boys, it was pressed on Hazlewood's short-lived Eb X. Preston Presents label. The fledgling label, Jimmy Delbridge, the hillbilly backing musicians, and Duane's budding singing career all fell by the wayside in short order. Yet fame and fortune was in the cards for Duane and the new cherry-red Gretsch guitar he'd begun toting to Phoenix session dates.

By late 1957, Duane was co-writing songs with Lee Hazlewood and leading a studio band he called The Rebels. It featured Buddy Wheeler on bass, Bob Taylor on drums, Donnie Owens on rhythm guitar, and a married couple, Al and Corky Casey, playing piano and rhythm guitar, respectively. At Hazlewood's urging, Duane began to play melody almost exclusively on his guitar's bass strings. This emphasis on the lower register gave The Rebels a most unusual sound. Hazlewood and his new partner, music publisher Lester Sill, thought it sounded commercial enough to record. Picking up on the Latin influences that were becoming rife in Rock music, guitarist and producer collaborated on a driving Rock 'n' Roll cha-cha-chá with a recurring clarion-like guitar figure. They titled it "Moovin' And Groovin." Sill and Hazlewood took The Rebels into Phoenix, Arizona's only recording facility, Ramco Audio, and cut the tune. "Ramco was a hovel," wrote Mark Ribowsky in his 1989 book He's A Rebel. "(It allowed for) no more than one track of recording tape, but Hazlewood worked wonders with echo and tape delay and reverb." Pop records in the 1950s tended to have reverb thicker than molasses; using echo to make a track sound bigger was hardly an innovation. However, Lee Hazlewood craved a distinctive echo sound. He got it by hauling an old, battered and abandoned water tank into the parking lot behind Ramco. He had engineer Jack Miller attach a microphone to the tank, pipe the sound of The Rebels' recording session inside it, and tape the result. This metallic, submerged submarine effect would become the trademark of Duane Eddy records.

After Lester Sill took the track to Hollywood's Gold Star Studios and overdubbed Plas Johnson playing a feverish sax solo, he started shopping it around to various labels. Most A & R men found the disc too off-the-wall for their tastes. Dot Records CEO Randy Wood reportedly thought it sounded "like someone trying to string telephone wire across the Grand Canyon!" Eventually, though, Harry Finfer of Philadelphia's Jamie Records decided to take a chance on it. "Moovin' And Groovin'" broke for a local hit straight out of the box, and its weird, watery ambiance soon caught the attention of national deejays. In the end, it rose no higher than #72 on Billboard's Pop chart, which was a major disappointment for all concerned. Momentum had been established, though, and Sill-Hazlewood productions had no intention of letting it slip away.

For Duane Eddy and The Rebels' next release on Jamie, Lee Hazlewood worked his water tank reverb technique to maximum effect. The Rebels sounded like they were playing from the bowels of an urban sewer system! The record's goose-stepping rhythm was funky like the sewer, too. Gil Bernal replaced Plas Johnson as sax player this time, and to add more body to the track, Sill and Hazlewood hired a local doo-wop group called The Sharps. The producers urged Al Frazier, Sonny Harris, Carl White and Rocky Wilson to clap hands and whoop it up while Bernal's sax wailed away. (Duane would return the favor by playing lead guitar on the group's Jamie single "Have Love, Will Travel.") The unfettered energy of this new platter was impossible to ignore, but Eddy and Hazlewood wanted to hedge their bet. Deciding that their song title needed to target a specific market, they called the new single "Rebel Rouser." With the loaded Civil War term "rebel" printed on the label twice, they hoped the tune would get lots of airplay south of the Mason-Dixon line. The gimmick worked; it got plenty of southern exposure, and from Dixieland to Hollywood and back across the Midwest to New England, "Rebel Rouser" broke for a solid smash. It took fourteen weeks, but the record firmly lodged itself in Billboard's Top Ten Pop and Rhythm and Blues listings.

Duane and the members of his band were elated; plans for a promotional tour were initiated. However, a single appearance on television would prove to be more valuable than a fortnight of tour dates. The stockholders of Jamie Records included a certain TV host named Dick Clark. As soon as he became aware of "Rebel Rouser," Clark was on the phone to Sill and Hazlewood, asking to book Duane on his popular "American Bandstand" dance music program. "Rebel Rouser" hadn't been issued in a picture sleeve, so the millions of teenage girls who comprised the show's core audience didn't know what to expect when Clark introduced the 20-year-old guitarist on July 24, 1958; was Duane Eddy old, like Bill Haley? Tubby, like Fats Domino? Scary, like "Screamin" Jay Hawkins? Stiff, like Pat Boone? They couldn't have been more delighted when out from behind the curtains walked a tall dreamboat with broad shoulders, wavy dark hair, a dazzling Colgate smile, bee-stung lips and seductive eyes. When his stammered answers to Clark's interview questions made it obvious that he was bashful, girls en masse fell in love with him. Duane Eddy was a hunk! Even better, he was a shy hunk, the kind of Rock 'n' Roll musician you could feel safe bringing home to Mama. Immediately following his charmer of a "Bandstand" appearance, "Rebel Rouser" passed the one million mark in sales.

Meanwhile, a problem had arisen; Duane learned that he wouldn't be able to take his studio cats on tour. Donnie Owens quit the group to embark on a solo career (Duane would play guitar on his Jamie hit "Need You" in late 1958), and the Caseys made it known that they didn't want to go out on the road. Duane drove to Los Angeles and quickly recruited a Rebels touring group. Mike Bermani took Bob Taylor's place behind the drum kit, "Teenage" Steve Douglas filled in for sax soloists Plas Johnson and Gil Bernal, and Ike Clanton, older brother of teen idol Jimmy Clanton, took over bass duties from Buddy Wheeler. Later recruits included brass player Jim Horn, drummer Jimmy Troxel and pianist Larry Knectel. All of them would eventually play on Duane's studio sessions, although Lee Hazlewood felt they weren't as talented as his Phoenix musicians. Within a few years, he'd be proven wrong, because most of these new Rebels developed into top session musicians. They would later log dates with Johnny Rivers, The Beach Boys, The Mamas and The Papas, The Fifth Dimension, Phil Spector's artist roster, and many, many other West Coast stars. They were also a big hit on tour, their surefooted Blues chops winning over even tough-to-please audiences like those at Harlem's Apollo Theatre. By early 1959, Duane Eddy and The Rebels were appearing at New York's Brooklyn Fox theatre on a bill with Fats Domino, Jackie Wilson and Bobby Darin, and headlining Dick Clark's "Rock 'n' Roll at The Hollywood Bowl" extravaganza.

Meanwhile, a problem had arisen; Duane learned that he wouldn't be able to take his studio cats on tour. Donnie Owens quit the group to embark on a solo career (Duane would play guitar on his Jamie hit "Need You" in late 1958), and the Caseys made it known that they didn't want to go out on the road. Duane drove to Los Angeles and quickly recruited a Rebels touring group. Mike Bermani took Bob Taylor's place behind the drum kit, "Teenage" Steve Douglas filled in for sax soloists Plas Johnson and Gil Bernal, and Ike Clanton, older brother of teen idol Jimmy Clanton, took over bass duties from Buddy Wheeler. Later recruits included brass player Jim Horn, drummer Jimmy Troxel and pianist Larry Knectel. All of them would eventually play on Duane's studio sessions, although Lee Hazlewood felt they weren't as talented as his Phoenix musicians. Within a few years, he'd be proven wrong, because most of these new Rebels developed into top session musicians. They would later log dates with Johnny Rivers, The Beach Boys, The Mamas and The Papas, The Fifth Dimension, Phil Spector's artist roster, and many, many other West Coast stars. They were also a big hit on tour, their surefooted Blues chops winning over even tough-to-please audiences like those at Harlem's Apollo Theatre. By early 1959, Duane Eddy and The Rebels were appearing at New York's Brooklyn Fox theatre on a bill with Fats Domino, Jackie Wilson and Bobby Darin, and headlining Dick Clark's "Rock 'n' Roll at The Hollywood Bowl" extravaganza.

"Rebel Rouser" continues

with Part Two.

.jpg)

Comments