The Technicolor Revolution (Part Two)

Lights! Color! Action!

Neon Rainbow

The Technicolor Revolution

by Hampton Jacobs

Herb Kalmus's production of The Viking, starring Pauline Starke and Donald Crisp, is the most impressive of all silent films ever shot in color; its visual glory even surpasses that of The Black Pirate. As Douglas Fairbanks' film had demonstrated, the dreamlike, ethereal look of two-color Technicolor was ideally suited to historical costume dramas. Kalmus's production crew made sure there was plenty of period costuming for viewers to feast their eyes on, and plenty of actors to wear it onscreen. At times, the movie's teeming battle scenes almost rival those found in the films of DeMille and Griffith. Technicolor even paid for a synchronized orchestral soundtrack to enhance the on-screen action. The finished feature was screened for M-G-M executive Irving Thalberg, and it left him breathless. He was so impressed, he convinced his studio to purchase the rights from Technicolor, and the company was subsequently reimbursed over $300,000 in production costs. As an official Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer release in 1928, The Viking wasn't the smash hit Herb Kalmus had hoped it would be, but nonetheless, he viewed it as an unqualified success. His company had recouped its investment, and the movie reviews were mostly glowing. Even more important, he knew that Irving Thalberg was highly respected in the movie colony; once news of Thalberg's enthusiasm for Technicolor's latest project had spread to other studio executives, good things were bound to happen. All he had to do was wait.

"THE PHANTOM OF SANTA FE"

produced by Pioneer Multicolor

a Technicolor rival

1931, re-released in 1936

He didn't have to wait long! Suddenly, Hollywood's biggest moguls were clamoring at his company's door again. Foremost among them was Jack Warner, CEO of Warner Brothers Pictures. With The Jazz Singer, he had proven the profitability of talking pictures; now Warner was eager to top himself by releasing hit movies that boasted both sound and color. Three subsequent films produced in 1929, The Desert Song (featuring color sequences only), Gold Diggers Of Broadway, and On With The Show (the first Technicolor movie released with synchronized dialogue) helped Warner Brothers dominate box office receipts that year. Rival studios panicked, fearing they were about to miss out on the Next Big Thing in movies. By January of 1930, the Technicolor Corporation had been contracted to photograph three dozen Hollywood productions, and found itself sitting pretty on a million dollar bank account. It was a heady time for Dr. Kalmus and his partners.

The 1930s kicked off with a slew of two-color Technicolor releases, the most significant being the costume dramas The Vagabond King (starring Jeannette MacDonald) and Song Of The West, the musicals King Of Jazz (which won an Oscar) and Sally, and the ribald comedy flick Whoopee, starring Broadway sensation Eddie Cantor and featuring elaborate Busby Berkeley dance sequences. However, Technicolor found that new problems came with its new visibility. The 1929 stock market crash had thrown the country into economic collapse, and it soon became apparent that the novelty of color wasn't enough to draw jobless people into movie theatres. Box office flops multiplied. What's more, many of the new color movies suffered from bad scripts and deplorable directing . . . and that included art direction. Scenes filmed in garish, clashing colors became so common, movie critics took to complaining of eye strain. Dr. Kalmus's wife Natalie, who served as Technicolor's chief color consultant, was particularly appalled at this development. For his part, Herb Kalmus was no longer satisfied with the implied realism of the two-color process. From the beginning, his goal had been true-to-life color, and despite what dozens of fawning reviews were claiming, red and green filters alone couldn't achieve it. The only way to reproduce a full spectrum of natural hues was with a three-color process. As contracts for new film productions failed to materialize, Kalmus realized it was do-or-die time: Only the success of Technicolor Process Number Four could save his company from bankruptcy!

made Technicolor look like money in the bank

It took technicians another three years to perfect the three-strip process (which exposed film through red, green and blue filters), but by the summer of 1932, it was finally ready for its debut. However, Technicolor's most spectacular innovation yet came very close to being dead on arrival. Hollywood was now in the depths of the Great Depression; studios were struggling to make a profit, and this new color process was almost prohibitively expensive. Herb Kalmus had door after door slammed in his face; at Paramount, M-G-M, Warner Brothers, Universal, and on all the other movie lots, he was persona non grata. He could only raise interest at animated movie studios, and even they were cautious. However, he reasoned correctly that some adventurous producer would be intrigued with the idea of color cartoons. That producer was Walt Disney. In late 1932, Disney released an animated short subject called Flowers And Trees in the new full-color process. Critics were ecstatic, audiences were enchanted, and the film industry would up giving the cartoon an Oscar. The same thing happened in 1933 when Disney's second color feature, The Three Little Pigs, hit theatres. Black-and-white cartoons became obsolete overnight, and just in time to fend off angry creditors, the Technicolor Corporation claimed a roster of steady animation clients. Live-action studios remained stubbornly resistant, though, until Jack Warner agreed to gamble again on the old two-color process. In 1932 and ‘33, his studio spiced up a pair of horror films with it, both starring a soon-to-be famous actress named Fay Wray. The most successful and best-remembered of the two movies was Mystery Of The Wax Museum.

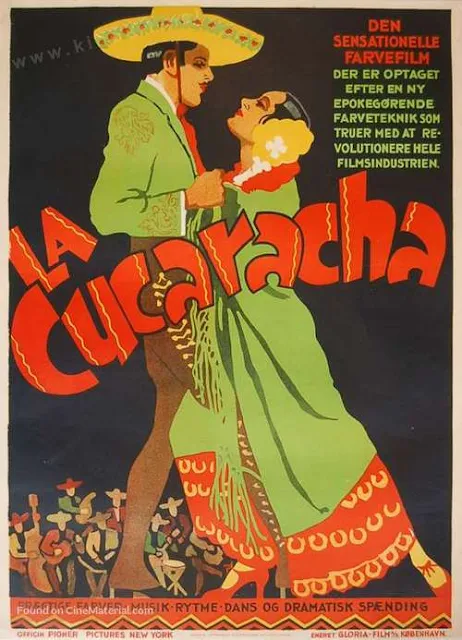

Triumph in the cartoon genre notwithstanding, the devastated American economy was almost too high a hurdle for Technicolor to clear. Salvation came in the form of two big-talking investors named Merian C. Cooper (director of the megahit King Kong) and Jock Whitney. Cooper and Whitney were bowled over by the sample live-action color footage Dr. Kalmus screened for them, and they contracted with Technicolor to photograph every movie they planned to release through the independent studio they'd co-founded. The two men may have been high-stakes gamblers, but they weren't beyond hedging their bets; in order to test the feasibility of their proposed venture, they decided that the first Pioneer Pictures release would be a film short. Character actors Don Alvarado, Paul Porcasi and Steffi Duna were engaged along with a Mexican dance troupe, and the cantina comedy La Cucaracha went before the cameras in early 1934. Cooper and Whitney gave their gambling impulses free reign during the production. They spared no expense; the final budget was in excess of $60,000, making La Cucaracha the most costly two-reeler filmed up to that time. Luckily for them, the money was well-spent. The combination of Mexican song and dance with splashy primary colors yielded a big hit, both commercially and critically. Hardly any reviewers bothered to comment on the comic storyline or exotic musical segments; they were too busy proclaiming the arrival of rich reds and true blues to the American cinema palette. Everyone agreed that this was the most vivid color process seen to date. Clearly, the limitations of two-color photography were now a thing of the past, and nothing underscored that fact more strongly than the Oscar awarded to La Cucaracha for Best Comedy Short Subject of 1934.

Pioneer Pictures only completed two full-length movies before going belly up: The historical drama Becky Sharp, and the period musical comedy Dancing Pirate. Neither made money. However, a three-strip Paramount Studios production called Trail Of The Lonesome Pine did turn a profit, and the time Technicolor staff spent working on all three productions taught them some valuable lessons. They discovered that camera glare was a problem with the new process, so certain costumes and props had to be color-treated before filming. A new kind of pancake makeup was needed to keep skin tones pure, so Max Factor began developing one in close consultation with Ray Rennahan and other Technicolor cameramen. Most important of all, film sets needed to be designed for color so that intense hues wouldn’t clash or distract audience attention from the storyline. Much to the chagrin of directors, Natalie Kalmus began to assert herself more forcefully on Hollywood movie sets. No production could begin without one of her color charts being on hand for art directors to reference!

"LA CUCARACHA"

1934

Armed with new expertise, the Technicolor Corporation was raring to go when Jock Whitney convinced maverick producer David O. Selznick to pick up Pioneer Pictures’ movie option. The deal brought with it something Dr. Kalmus and his associates had been craving since their ill-fated collaboration with Douglas Fairbanks: Major movie stars willing to be filmed in color. For his first production, Selznick cast Charles Boyer and Marlene Dietrich in the lead roles. Miriam Hopkins had starred in Becky Sharp, and an up-and-coming player named Henry Fonda had led the cast of Trail Of The Lonesome Pine, but in 1936, neither actor could match Boyer and Dietrich’s international star power. Miss Dietrich’s ravishing beauty and glamorous costumes proved to be the main selling points for Selznick’s Garden Of Allah, and sell it did. The lavish desert romance broke big at the box office, and while it didn’t win any Oscars, the Motion Picture Academy saw fit to honor it with a special color photography citation. This led directly to the establishment of a Color Cinematography Oscar in 1939.

Profits + Star Power = a formula that finally convinced Hollywood's skeptical studio executives that Technicolor was bankable. Accordingly, the late 1930s were awash in color spectacles, several of which have attained the status of legend: Walt Disney's Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs; Warner Brothers' The Adventures Of Robin Hood, Dodge City and Private Lives Of Elizabeth And Essex, all starring Errol Flynn; 20th Century Fox's Drums Along The Mohawk, another box office smash for Henry Fonda; M-G-M's timeless Wizard Of Oz featuring Judy Garland; and David O. Selznick's classic melodramas A Star Is Born and Gone With The Wind. Among the rack of Oscars awarded to the latter film was Technicolor's first for photographic excellence. The avalanche of acclaim these productions garnered flung open the door for a multitude of color extravaganzas, which held forth on movie screens with ever increasing frequency through the 1940s and '50s. Female stars like Betty Grable, Doris Day, Esther Williams, Carmen Miranda, Maria Montez and Maureen O'Hara became known for appearing almost exclusively in color films. By 1955, it was rare to see a musical or costume drama filmed in black-and-white, and by the late 1960s, movies in monochrome had become the rarity Technicolor films once were. Now, over 100 years after Thomas Edison experimented with clumsy hand-tinting, the tide has turned completely in color's favor.

Frank Morgan may have played the Wizard Of Oz in the famous 1939 movie, but he doesn't deserve the title. Herb Kalmus was the real wizard! Without him, there might never have been a yellow brick road for Judy Garland to dance along, or sparkling ruby slippers for her to wear. It was Dr. Kalmus's vision, his brilliance, his tenacity and his Technicolor wand that transported Hollywood over the neon rainbow.

"UNDER A TEXAS MOON"

starring FRANK FAY

starring FRANK FAY

featuring MYRNA LOY

early Technicolor from Warner Brothers

1930

Quotes and other information for this essay were taken from the book Glorious Technicolor: The Movies' Magic Rainbow by Fred E. Basten (Technicolor, 2005). It contains a complete list of Technicolor film productions released between 1917 and 2005, as well as hundreds of stunning color publicity stills.

.jpg)

Comments