Mad Hot Book Review #2

Before "Brokeback Mountain" There Was . . .

Song Of The Loon

by Richard Amory

(Arsenal Pulp Press, 2005)

book review by Hampton Jacobs

Over thirty years before E. Annie Proulx won national acclaim for her 1997 short story "Brokeback Mountain," and nearly forty years before that story was turned into an Oscar-winning motion picture, a book written by an obscure pulp fiction author took the paperback publishing world by storm. The most successful Gay fiction novel of the 1960s, Song Of The Loon is reputed to have sold over 100,000 copies. It was the underground equivalent of a New York Times bestseller in its day. Its popularity among homosexual and enlightened heterosexual readers was so immense that it spawned two sequels, a not-bad parody (Fruit Of The Loon) and an independent "art house" film.

Editor and critic Michael Bronski stresses the book's historical significance and groundbreaking nature. He calls it "a completely original and dazzling novel that marked a turning point in the evolution of Gay literature . . . it was a cultural milestone (that) retains its resonance and power today." At a time when love between men was criminalized and widely considered a pathological disorder, Song of The Loon conveyed a strong message to the contrary. That message, in Bronski's words, was that "only by loving oneself, essentially accepting the fact that (being) Gay is good, can one ever love other people and be at peace with the world."

Novels with homosexual main characters have been available in the United States at least since the 1920s. Written mostly by heterosexual authors, their tone was more often than not tragic. Lesbians and Gay men were portrayed as doomed, haunted figures, invariably fated to loneliness, unhappiness, depravity, blackmail, mental illness and/or death. The Well Of Loneliness, Radclyffe Hall’s controversial 1928 classic is probably the best example of this dreary tradition. You can also find doomed homosexual types in theatrical works like The Children’s Hour by Lillian Hellman (1936) and Tennessee Williams’s Suddenly Last Summer(1958).

Slowly but surely, the tragic tone of Gay fiction began to change, helped along by progressive Gay writers like Gore Vidal and Mary Renault(though ironically, the success of “Brokeback Mountain” may spark a revival of the tragic Gay love story). By the early 1960s, such books were more likely to be published in paperback than hardback, and their sexual content was far more explicit than had previously been allowed. The stage was set for the revolutionary concept of same-gender love that Song Of The Loon presented. Agitated by a burgeoning Civil Rights movement and the spirit of social protest in the air, homosexual men were ready for it.

Richard Wallace Love wrote paperback fiction under the pen name Richard Amory. A homosexual man himself, Love hated the kinds of sensational Gay novels that proliferated in the 1950s and '60s; they sported lurid titles like Hot Pants Homo, Warped Women, Cocksure and Train Station Sex. He felt that stories about Lesbians and Gay men could and should reach for a higher standard. The mores of the day ensured that paperback books with homosexual protagonists would be marketed as pornographic titles; there was nothing he could do about that. His editor demanded lots of sexual content, and there was nothing he could do about that, either. Even so, he was determined to write Song Of The Loon in such a way that it could not be dismissed as pornography.

The sexual content would serve a purpose other than prurience, and the story itself would have real literary merit. Love structured his first novel in the style of Spanish pastoral novels of the 16th century; in particular, he was influenced by an erotic narrative written by Gaspar Gil Polo called La Diana Enamorada. Proceeding at a leisurely pace, he wrote his masterwork in 1964 and 1965 while working as a graduate teaching assistant at San Francisco State University. The first of his three Loon books was published by San Diego-based Greenleaf Press in 1966.

Despite the heavily romantic tone, no women characters appear or are discussed in Song Of The Loon. Certain scurrilous biographers of Richard Wallace Love have used this fact to suggest that he was a misogynist. Not true! Love supported the Feminist movement and was definitely not a woman-hater. In a 1970 interview, he explained that the exclusion of female characters allowed him an economy of storytelling he wouldn't have had otherwise. One can argue that the integration of women characters might have added an interesting dynamic to Song Of The Loon. On the other hand, the all-male setting spared readers from having to read about men cheating on or otherwise abusing their wives, as happens in "Brokeback Mountain."

A fascinating and superbly-written sequence describing an Indian spirit quest proves pivotal to later events. By the end of the novel, the lives of several major characters are transformed. Ephraim McIver's mountain journey ends up being about self-acceptance, and about overcoming the fear and confusion he feels since fleeing Clarence Montgomery's drunken rages. It's not a journey for prudes, though! Ephraim becomes physically intimate with nearly every man he encounters. However, true to his literary intentions, Richard Wallace Love wasn't just trying to make his readers drool over steamy copulation scenes. He wanted to begin a dialogue about the nature of true love, and about the possibility of loving several people at once.

A key passage appears right after Ephraim's first erotic encounter with an Indian named Singing Heron. Alarmed when the Indian reveals that he already has a lover, he worries that the man will seek revenge on them. Singing Heron responds: "You suffer from the White man's disease . . . it is called jealousy, but sometimes I think it is called selfishness. If I love one man, can I not love another at the same time? If one man has filled my heart with love, can I not share it with another? If I make love to you, that does not mean that I love another less. I do not want to own you as I would a puppy . . . that isn't love, Ephraim." Song Of The Loon is filled with provocative socio-political messages like this. Given what took place in years subsequent to its publication, these messages would appear to have resonated strongly with Gay male readers.

Richard Wallace Love's unique portrayals of homosexual relationships in 1966 presaged several important developments in what would later come to be called "Gay Culture." For example, the formation of a community of men who openly identified as Gay; the freewheeling sexuality that came to characterize that community; the widespread belief that Gay men really were men, not male perverts or women trapped in male bodies; the phenomenon of "Clones," large groups of rugged, masculine-identified Gay men who rejected effeminate behavior; the rise of a rural-based "Radical Faerie" movement that emphasized country living and the creation of homoerotic art, music and poetry; the spread of "Bear Culture," whose portly adherents decried the worship of "perfect" male bodies; and the growth of a "Longhaired Men" enclave within both Radical Faerie and Bear Culture, whose members promoted and embraced romantic male imagery. Precedents for all of these societal changes can be found to a greater or lesser extent in the pages of Love's first novel.

The fantasy world depicted in Song Of The Loon where Gay men celebrate same-gender love pretty much came to life in San Francisco, New York City and other large metropolitan areas during the 1970s. To be sure, it was a world far different from the secretive one Richard Wallace Love came of age in; between 1957 and 1969, he lived the double life of a married father of three who had homosexual affairs on the side. He belonged to an earlier generation of Gay men who saw their sexuality as something that should be hidden away; yet, he was a visionary.

Regardless of how influential Love may or may not have been in the evolution of a positive Gay identity, there can be no doubt that his work had a powerful impact. The book he's remembered for, as well as a writer's circle he founded called The Renaissance Group did much to legitimize the Gay fiction genre. His Loon Society sequels, Aaron's Song and Listen! The Loon Sings were published by Greenleaf Press in 1968 and 1969, respectively. Other "Richard Amory" novels include Longhorn Drive, A Handsome Young Man With Class, Naked On Main Street (all published in 1969), Frost (1971) and Willow Song(1974). He died, reportedly in San José, California, in 1981.

Historians hail Song Of The Loon as a milestone in the Gay Liberation movement, and that‘s understandable. However, Richard Wallace Love's novel is so finely-crafted, and so compelling, its appeal need not be limited to homosexual men. When the book was excerpted in Michael Bronski’s fiction anthology Pulp Friction(St. Martin’s Press, 2003), popular demand prompted its reissue by Arsenal Pulp Press in 2005. (At this writing, it’s still selling briskly on amazon.com.)

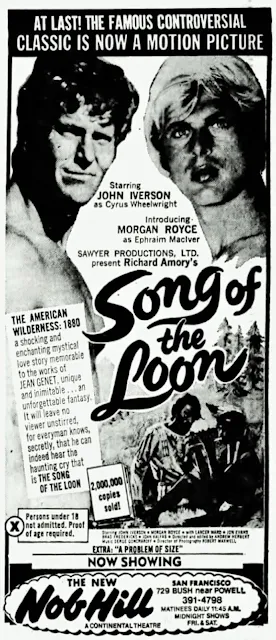

The existence of the aforementioned film adaptation provides further evidence of its broad appeal. Slapped with an "X" rating by the Motion Picture Assocation, Song Of The Loon opened at various “specialty” houses in the summer of 1970. It starred Morgan Royce as Ephraim McIver and was directed by Andrew Herbert, who would later work as a film editor on such mainstream Hollywood movies as Up The Academy(1980). Even with male frontal nudity on display the film didn‘t make much money, but that’s probably because it wasn’t faithful to the story or the characters. Ephraim's character died at the end of the movie(he doesn‘t in the novel), and all the Native American roles were played by White actors! What’s more, the supposedly racy man-on-man sex scenes were even tamer than the one between Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhall in last year's major studio adaptation of "Brokeback Mountain." Still, interest in this film has remained high enough to justify its release on video a few years back, and copies of it have become much-sought-after collector’s items.

Song Of The Loon deserves to be rediscovered by contemporary erotic fiction fans, and without question, it should be re-filmed someday. Done properly, it would make an excellent “chick flick!” Unfortunately, the American filmgoing public isn’t even close to being ready for Richard Wallace Love's radical visions yet; the crass Gay cowboy jokes that have multiplied in the wake of Brokeback Mountain’s success indicate as much. The typical audience at a suburban multiplex cinema would surely find a Song Of The Loon movie hard to digest; a big screen version of TV's “Will And Grace” would probably be more to its taste. It's easy to predict what kind of reaction religious right wing elements would have . . . just imagine what Pat Robertson might feel forced to say! (On second thought, let's not imagine that.)

Even if released in today's tolerant climate, it's not inconceivable that such a film would still be rated "X." Maybe in our children’s or grandchildren’s lifetimes, serious same-gender love stories will not seem so threatening. Until then, this remarkable Gay western novel from the 1960s will remain a major media event waiting to happen.

.jpg)

Comments