The Tico Records Story, Parts One and Two

King of The Cha-Cha Mambo!

The History of George Goldner's Tico Records

by Hampton Jacobs

Part One:

THE BIRTH OF TICO RECORDS

AND THE TWO TITOS

There's probably no form of popular music more under-appreciated in the United States than Latin music. Yet, it's hard to imagine a time when it wasn't heard here. Given that large sections of this country were once Mexican territory, Latin songs and dances have been a part of our cultural tapestry for a very long time! Over the last 80 years, their influence on Country, Jazz, Rock, Reggae, Rhythm and Blues, Disco and even Broadway show tunes has been profound; you can hear it in songs as diverse as "San Antonio Rose", "St. Louis Blues", "Spanish Harlem", "Doo Wah Diddy Diddy", "Turn The Beat Around" and Irving Berlin's "Heat Wave".

North Americans en masse first became fascinated with Latin rhythms in the second decade of the 20th century, when professional dancers Irene and Vernon Castle imported Argentina's tango to New York City. It intensified during the 1930s, with hit records like "El Manicero (The Peanut Vendor)" by Don Azpiazú's Havana Casino Orchestra, hit movies like Flying Down To Rio in which Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers demonstrated the rhumba, and the splashy Broadway débuts of Brazilian bombshell Carmen Miranda and conga king Desi Arnáz. By then, many Cuban, Puerto Rican, Brazilian, Mexican and Spanish migrants were taking advantage of the Latin craze by forming their own orchestras. Their interaction with Jazz musicians sowed the seeds of the mambo and the cha-cha-chá in the early 1940s, and made possible the flourishing of Latin music meccas like New York's Palladium Ballroom and Hollywood's Million Dollar Theater.

Many of these Latin Pop pioneers got the chance to commit their music to wax. Major record labels such as RCA Victor, Columbia and Decca had been waxing Latin music almost since the advent of recording technology. However, with the outbreak of World War II, materials used to make 78 RPM records were severely rationed. The majors opted to put their limited resources behind "mainstream" (Anglo) acts and many Latin artists lost their recording contracts. In the '40s, the first nationally-distributed independent labels devoted to Latin music came into being . . . SMC, Mardi Gras, Verne, Coda, Seeco and others. Tico Records was arguably foremost among these companies.

Inner sleeves from early Tico album releases had the following message emblazoned on them in huge blue letters: Mambos and Cha-Chas! The Best in the World for Your Listening and Dancing Pleasure. It read like typical record company hype of the period, but it was surprisingly true. Tico Records could legitimately boast of marketing the best Latin dance music around. Research into the history of the label unearths a familiar name: George Goldner. He was one of the most important figures in the development of Rock 'n' Roll as we know it today. An early R & B producer and record executive, Goldner founded such seminal Rock labels as Rama, Gone, End, and later, Red-Bird Records. He made possible the success of early Doo-Wop groups like The Crows, The Cleftones, and most famously, The Teenagers featuring Frankie Lymon. His 1957 production of The Chantels singing "Maybe" is widely believed to have launched the Rock 'n' Roll Girl Group genre. Many historians consider him the patron saint of R & B vocal group music. Yet, in his book Rhythm and The Blues, former Atlantic Records executive and Rock 'n' Roll Hall of Fame inductee Jerry Wexler calls Goldner "the phonograph record's King of Salsa". Both perceptions of the man are correct, because Latin artists paved George Goldner's path to Rock 'n' Roll.

In a 2001 Vanity Fair article, respected R & B songwriter and producer Jerry Leiber remembered him as an immaculately groomed man who "looked like (actor) Adolphe Menjou . . . not a hair out of place". Journalist Tony Scherman described him in 1993 as a suave ladykiller who "dressed exquisitely and was fond of Tiffany cigarette cases". A native New Yorker born in 1918, Goldner first made his living as a garment dealer. However, dance music was his secret passion. He abandoned the rag business in the early 1940s to run dance halls, which were thriving due to the popularity of Swing bands. He loved to dance himself, and according to some sources, he even taught dancing for a while.

Goldner's wife Gracie was Puerto Rican, and Spanish-language recordings often played in their home. The Goldners were no doubt among thousands of New Yorkers who flocked to ballrooms in order to enjoy exciting live sets by the city's finest Latin musicians. "Everyone danced mambo and cha-cha", pianist and future Tico recording artist Alfredito Valdés, Jr. would recall decades later. "(Bands would be) at The Palladium, The Manhattan Center, (The) Riviera Terrace". The Palladium, located at 53rd Street and Broadway, billed itself as "Home Of The Mambo", and was by far the most popular spot for Latin dancing. Anyone from New York City transit workers to actors James Dean, Eartha Kitt and Tina Louise might be seen there, brushing up on the latest mambo variations. It was smarter than the average ballroom, as Downbeat Magazine's Nat Hentoff detailed in a 1954 column: "The $1.75 admission entitles the adventurous patron to mambo instructions early in the evening, plus an amateur contest for mambo dancers, plus a professional mambo show from eleven to twelve (midnight), plus dancing . . . the consensus of the clientele seems to be that this is far better exercise than bowling or turning off the TV commercials."

Enchanted by the music played at the Palladium, and at his own establishments, Goldner found himself wanting to record it. In 1948, he formed a partnership with radio personality Art "Pancho" Raymond, who hosted a Latin music show on Station WLIB. The name of the record label they founded was derived from the 1943 Xavier Cugat hit "Tico Tico No Fubá". Raymond's involvement notwithstanding, Tico Records was always George Goldner's baby. With little more to his credit than chutzpah and enthusiasm, he dove headlong into the treacherous waters of music recording, marketing, and promotion, learning (and making up new rules) as he went.

Art Raymond's experience in the record business counter-balanced Goldner's lack of same, but partnering with a disc jockey wasn't necessarily a smart move. Given Raymond's high-profile involvement with the company, WLIB was vulnerable to conflict-of-interest charges if he played Tico releases. What Goldner felt he needed in order to access radio playlists was a few silent partners. Partners like Dick "Ricardo" Sugar, a popular deejay who was preparing to launch his own Latin music show on Station WEVD. He decided to purchase blocks of airtime from Sugar, a practice which, though legal in the '40s, would be eventually be denounced as "payola" and prohibited. However, from 1948 on, George Goldner actively cultivated a reputation among New York deejays as Mr. Pay-For-Play!

Among other unofficial partners in Tico Records were jocks Bob "Pedro" Harris and Matty Singer, "The Humdinger" (one of the label's early single releases was called "The Matty Singer Mambo"). Throughout his career, George Goldner would maintain close ties with radio people; in a few more years, he'd establish a mutually beneficial relationship with pioneering Rock jock Alan Freed. At this early stage, Dick Sugar was the main person he counted on to provide an outlet for his product, and he certainly must have been encouraged when Sugar christened his program "Tico Tico Time"! Years later, the deejay would allow that he did so "in honor of Tico Records".

Goldner and Raymond set up offices at 659 Tenth Avenue in Manhattan, and went out hunting for talent. There was plenty to be had! Swing had become passé, and dozens of Latin bandleaders were rushing to fill the musical void; almost overnight, it seemed, the mambo craze was in full bloom. There were lots of cocky young Hispanic musicians around town, and all who hadn't already been snatched up were anxious to get into a recording studio. In a stroke of incredible good luck, among the first acts Goldner and Raymond signed were two bandleaders who would become legends of Latin music: Percussionist Tito Puente and singer Tito Rodríguez, both veterans of New York's "cuchifrito" (Latin club) circuit, as well as alumni of important society bands like those of Noro Morales, José Curbelo, Pupi Campo and Xavier Cugat. The high quality of their Tico recordings would do much to build their respective reputations.

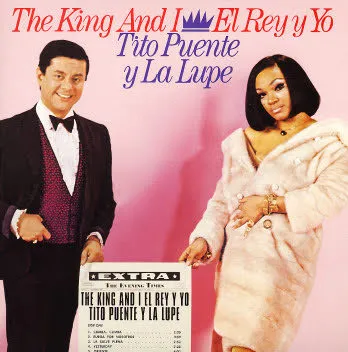

Tito Puente was unquestionably Tico's star, both in the label's earliest years and much later, near the end of its existence. Journalist Max Salazar claims that Puente cut nearly 80 different recording sessions for Tico in its long lifetime. He started his own group after a long period of apprenticeship in various New York bands. A master timbalero who also played piano, vibraphone and brass, Puente was an excellent arranger and a top-notch showman. These qualities made him a headliner at The Palladium, as well as a consistent winner of Latin music polls. "Tito Puente was to the timbales what Buddy Rich and Tony Williams were to Jazz drums," author and percussionist Jim Payne writes. "He combined the snare drum and drum set techniques of (Jazz) with the traditional Cuban (percussion) style, and with innovation . . . he took performance on the timbales to a new level." Goldner recognized his talent right away, and gave him maximum creative leeway at record dates.

In the fall of 1949, Puente gave Tico its first big (regional) hit, "Abaniquito". After Dick "Ricardo" Sugar began giving the single regular airplay on his show, it was pounced on by Latin music deejays all over the East Coast. Lead vocals on this incendiary mambo number were sung by Cuban sonero Vicentico Valdés, who would record for Tico as a solo artist in later years; Latin Jazz pioneer Mario Bauzá made a guest appearance on trumpet. Among Puente's other early hits was the sizzling "Mambo Macoco", the groundbreaking "Vibe Mambo" and his cookin' version of the Cuban standard "Caramelos."

Goldner found himself supervising a landmark recording after Puente convinced him to schedule a session for a first-of-its-kind all-percussion album. There was nothing in the studio but Latin percussion instruments, Puente, his bandmates Ramon "Mongo" Santamaría, Carlos "Potato" Valdés and William "Willie Bobo" Correa, and a big bottle of rum which they passed among themselves. When the night was over, they'd cut Puente In Percussion, a classic disc that became the template for hundreds of subsequent Latin recordings. Other highly-regarded (and, collectors be warned, high-priced) Puente albums for Tico include Mamborama, Cha-Cha-Chás For Lovers, Dance The Cha-Cha-Chá, Puente In Love, Tito Puente Swings/Vicentico Valdés Sings, and Mambo With Me . . . and those are just his 1950s releases!

Tito Rodríguez also played percussion, but made his biggest impact as a singer. The brother of popular Puerto Rican vocal star Johnny Rodríguez, Tito came to New York in the late 1930s to follow Johnny into the music business. He took a job as featured vocalist with the popular society band of Enric Madriguera in 1941, then landed a spot the following year with the orchestra led by America's most celebrated Latin bandleader, Xavier Cugat. His spirited performance of "Bim Bam Boom" was one of Cugat's finest Columbia releases of the '40s. After leaving Cugie's employ, Rodríguez did much session work in-between brief stints with various other bands. After suddenly being fired from the José Curbelo Orchestra in 1947, he decided to start his own group, The Mambo Devils. Expanding from a combo to a ten-piece orchestra the following year, they were booked for an extended gig at The Palladium Ballroom, where they developed an avid following.

George Goldner produced a reconstituted version of Rodríguez's group under the name Los Lobos del Mambo, and scored bestsellers with such sides as "Mambo Gee Gee"(otherwise known as the"George Goldner Mambo"), "Mambo Mona (Mama Guela)", "La Renta" and the risqué "Chiqui Bop". Tito Rodríguez recorded for Tico between 1949 and 1958, leaving for a time to cut sides at RCA Victor, returning, and then leaving permanently in 1960 for the United Artists group of labels. There he would record his most acclaimed albums, Live At The Palladium and Tito Rodríguez Returns To The Palladium: Live!, and redefine himself as primarily a singer of romantic tunes. It's probably the recordings he made during this period that compelled Latin bandleader/writer Bobby Sanabria to compliment his "unique Jazz-influenced phrasing". However, his early Tico sides established him as a top contender in the mambo/cha-cha sweepstakes.

"All the (Latin) singers were influenced by Tito's style", stated singer Cheo Feliciano, one of many who considered him a mentor. "Everybody wanted to be Tito Rodríguez! He was the model for not only singers, but for bandleaders. He was a very fastidious dresser, and he demanded that his band look good at all times". The adjectives "polished" and "professional" certainly do spring to mind at the mention of his name. Notable sidemen on his sessions included pianist Joe Loco, conga player Luis Miranda, trombonist Billy Byers, saxophonist Lenny Hambro and trumpet player/arranger Harold Wegbriet. Just so everybody knew how much he valued his musicians, he cut a Tico album of instrumental boleros called Latin Jewels. However, his fans preferred albums like Wa-Pa-Cha, heavy on dance beats and not stingy with the Rodríguez vocal magic.

Every ballroom dance enthusiast in New York knew about The Palladium's "two Titos", so there was a consumer base ready and willing to buy 78 RPM singles by them. Puente and Rodríguez pumped out product on a regular basis, and the label was off to a great start. George Goldner found that he loved going into the studio with artists. The sound of hot Latin rhythms coming through the audio speakers was like an elixir to him. In 1987, Rock historians Mike Redmond and Steve West described the typical Goldner recording date: "Sessions took place in small, rectangular rooms with a small control booth at one end. Goldner and the engineer would monitor from the booth . . . the rest of the studio was occupied by the band and the singers, with a screen between them to prevent the sound from bleeding through. Three microphones were usually employed: One for the band, one for the lead singer and one for the (backing vocal) group". As he gained experience in the studio, Goldner became known for subjecting musicians to dozens of takes until he got exactly the result he wanted. His favorite part of recording sessions was playback time, according to Pop songwriter/producer Jeff Barry, who worked with him in later years. "He would listen with his eyes closed," Barry says, "and when the record was over, he would, when he was particularly excited, pick up the chair he was sitting on, and throw it against the wall!". Busted furniture must have been plentiful at early Tico sessions; a lot of exceptionally good dance music was cut, more than enough for Goldner to get excited about.

Then, in 1950, matters suddenly took a turn for the worse. Disagreements over money and/or creative direction led to a falling out between him and Art Raymond. Recording sessions were halted indefinitely; Puente, Rodríguez and Tico's other artists had little choice but to make deals with other labels. It took a year for Goldner to settle with Raymond and buy out his interests. Desperately in need of new funding, he turned to Joe Kolsky, a shady New York nightclub owner. Kolsky became an increasingly powerful silent partner in Tico Records as Goldner struggled to lure his back his old acts. He succeeded in signing Puente and Rodríguez to new contracts, and in the process, he found a new star: Joe Loco.

Since the late 1930s, Joe Estévez, Jr. had been a sideman with almost every major Jazz and Latin orchestra you could name. Tommy Dorsey, Xavier Cugat and Machito were some of his former employers. His nickname, translated as "Crazy Joe", came either from his sometimes erratic behavior or from a song that he co-wrote with Machito in the 1940s called "Cada Loco con Su Tema". Count Basie and Duke Ellington's work provided Estevez's inspiration, and of all Latin pianists of his era, he was the most popular with Jazz lovers. That was the result of his extensive Jazz background, and of his penchant for avoiding Latin tunes. He preferred to give Pop and Jazz standards like "How High The Moon" and "Bei Mir Bist Du Schön" the Latin treatment, a practice which reportedly enhanced his "crazy" reputation among peers.

Estévez came to Tico as a member of Tito Rodríguez's orchestra, but George Goldner was so impressed by his piano playing, he encouraged him to cut some solo sides. This yielded a hit single in 1952, a very atmospheric version of "Tenderly". Its enthusiastic acceptance on Jazz radio prompted Estévez to go out on his own. He formed a popular quartet with vibraphonist Pete Terrace, bassist Jules Andino, and bongó player Bobby Flash that became a fixture in New York Jazz lounges. While he was a Tico artist for less than three years, Joe Loco cut a wealth of great instrumentals for the label that filled out albums and compilations for years to come. Piano ballads like "Tenderly" were the norm for him, but you can't beat themes like his conga-pounding remake of "Hallelujah" for danceability.

Part Two:

MAMBO USA AND MORRIS LEVY

Goldner embarked on a frenzy of recording activity in 1951, making up for lost time. He and engineer Allen Weintraub practically took up residence at Bell Sound, which, along with Broadway Studios and A & R Recording, was one of his favorite recording sites for Tico sessions. The following year, the label issued 27 ten-inch record albums on Tito Rodríguez, Tito Puente, Leal Pescador, Joe Loco, Pupi Campo, and two anonymous groups of pick-up musicians, Los Rumberos de Cuba and the Tico Orchestra, culled from both new and old recording sessions. By 1956, the records were selling briskly enough for Tico to inaugurate a 12-inch LP series. No less than thirty long-players hit the market that year; it was an all-time production high!

Goldner continued to expand his artist roster. Conguero Mongo Santamaría took a break from Tito Puente's band to cut a solo session, and vibraphonist Pete Terrace quit Joe Loco's band to form his own quintet, The Latin Boys. However, Goldner hardly needed to cannibalize existing acts to acquire new talent! It was literally flocking to his door. By 1954, his new signings included three veteran Cuban bandleaders: José Fajardo and Rosendo Ruíz, Jr., who specialized in the hot new rhythm called cha-cha-chá, and Arsenio Rodríguez, whose lusty guitar-playing added a piquant new flavor to the mambo. Also welcomed to Tico was Alan "Alfredito" Levy, a Jewish percussionist whose mambo band ranked with the best. From the Dominican Republic came Ricardo Rico and his merengue band, and from The Palladium Ballroom bandstand came Machito and His Afro-Cubans. With Machito's signing, George Goldner managed to corral all three of the Palladium's biggest stars.

The beauty of having an act like the Afro-Cubans on your label was that it was like getting three stars in one package: Frank "Machito" Grillo and his sister Graciela Pérez, two incredibly charismatic vocalists, along with their brother-in-law, music director Mario Bauzá, an unapologetically progressive horn arranger. Bauzá had roots not only in Latin music but also in the great Swing ensembles of Cab Calloway and Chick Webb. He hung out with guys like Dizzy Gillespie, Buddy Rich and Charlie Parker, and there was no telling who'd show up to lend a hand on record dates Bauzá supervised.

After singing for Xavier Cugat, Noro Morales, Alberto Iznaga and other bandleaders, Machito had his fill of working for other people. He resolved to form his own band in 1940, recruiting Bauzá the following year. (Or, it was Bauzá's idea to form the band and he recruited Machito . . . it depends on what source you consult.) By the time Graciela arrived from Cuba in 1943 to substitute for her brother, who'd been drafted into the Army, the Afro-Cubans had been installed as the house band at Manhattan's Club La Conga. The club broadcast their sets over station WOR, and they became a sensation. Bauzá's fusion arrangements won them the patronage of important Jazz disc jockeys like Fred Robbins, and the admiration of established Jazz stars like Stan Kenton. In 1947, promoter Federico Pagani hired them as one of three house bands at The Palladium, where they came under George Goldner's direct scrutiny.

Machito and company began their decade-long tenure at Tico Records with a 10-inch album of cha-cha-chás, and each successive release got hotter and hotter. The hottest was probably "Sí, Sí, No, No", a record in which Graciela vocally approximated an orgasm while Machito gleefully egged her on. A live recording originally released on Columbia Records, it became an X-rated smash throughout Latin America, anticipating by at least twenty years similar hits by Jane Birkin, porn star Marilyn Chambers and Donna Summer. The Afro-Cubans recut their 1949 cult smash "Asia Minor" for Tico with excellent results, and also essayed an ambitious album of songs inspired by the movie version of Ernest Hemingway's novel The Sun Also Rises. Led by a family of proud Black Cuban musicians, their albums, singles, and live performances were as popular among African-Americans as they were among Latinos. Black audiences may not have understood all the words, but they couldn't fail to recognize their cultural idiom whenever Graciela stepped to the microphone and screamed: "Listen, listen, honey . . . ¡qué sabroso está!"

While the ink on Machito's contract was still wet, George Goldner was finalizing plans for the most ambitious Latin music extravaganza yet mounted in this country. As conceived by Goldner and concert promoter Irving Schact, "Mambo USA" was to be a nationwide tour featuring the best mambo bands and dancers working in New York City. The bill would include over forty artists, stopping to perform in 56 cities. Predating by nearly a decade similar Rock 'n' Roll tours by Berry Gordy's Motown Revue and Dick Clark's Caravan of Stars, it was an ambitious attempt to give these artists some nationwide exposure, as well as promote the latest Tico Records releases.

Goldner and Schact gave New York a tour preview on 20 February 1954, booking Carnegie Hall for a "Mambo/Rhumba Festival". Tito Puente, Joe Loco and Pupi Campo headlined the sold-out date, with the Phillips-Fort Dancers stepping fancy for the crowd, Cuban percussionist Candido Camero holding forth with his shirtless-and-covered-in-baby-oil conga drum routine, and singers Miguelito Valdés and Myrta Silva appearing as special guests. A week later, Tito Puente and Joe Loco kicked off a mini-tour at Brooklyn's Paramount Theater, and in July, Goldner sent Machito's Afro-Cubans on a three-week jaunt to whet the public's appetite a little more. It took the better part of a year to get the logistics down, but "Mambo USA" finally hit the road that fall.

Four decades later, Max Salazar spoke with Pete Terrace, one of the tour participants. "The tour began in late October", Terrace remembered. "On the bill was Machito's orchestra, Graciela, Joe Loco's Quintet, dancers Mike and Nilda Terrace, the Facundo Rivero Trio and the Mambo Aces (a duo comprised of dancers José Centeno and Anibal Vásquez)". Actor/singer Carlos Ramírez, Mexican comedy star Tin-Tán, and several other Latin dance teams also performed. Reportedly, Pérez Prado and His Orchestra joined the tour for selected dates on the West Coast. "We performed in Philadelphia, Boston, Cleveland, Chicago, Washington, DC, Miami Beach, San Francisco, St. Louis, and other cities in Texas. In most of the cities, the turnout was disappointing. Some nights, we were playing to less than twenty people sitting in the audience!"

Poor turnout was bad enough, but another problem, blatant racial discrimination, was worse. Pete Terrace: "Most of the musicians travelled in a bus marked 'Mambo USA', and when we stopped to eat, we were refused because of the dark-skinned musicians. Julio Andino, our Afro-Cuban bass player, developed an ulcer . . . the discrimination (he) experienced made him ill." Meagre box office receipts and the musicians' discontent over treatment they received in segregated cities ended the tour prematurely. If any live performances were taped, none ever saw release. However, George Goldner did issue a 10-inch Joe Loco album titled Mambo USA, featuring the peppy theme song and other numbers Loco had performed onstage. A positive result of the tour was that many people in the South and Midwest got a chance to see Mambo bands live in concert for the first and possibly only time. At the end of the day, Tico Records more likely than not derived some promotional mileage out of it; still, the thousands of dollars lost in the debacle taught Goldner a stiff lesson about the limits of Latin music's appeal outside its home base.

Tico released its first and only soundtrack album in the late '50s. It featured a group called The Boataneers playing Bahamian music heard in United Artists' tropical romance flick Island Women. This recording, along with those of Ricardo Rico and Mongo Santamaría, was folkloric in nature (in fact, Santamaría's Changó is said to be the first Afro-Cuban folk album ever issued in the United States). These albums sound quite rustic compared to the typical Tico release. Other Latin label owners craved musical authenticity, and didn't seem to mind if their product sounded like it had been taped on old-fashioned wire machines in the Guatemalan jungle. Not George Goldner! Recorded in state-of-the-art studios with impeccable arrangements, his Tico tracks were bold, sassy, and tailored strictly to the tastes of big city consumers. He and Allen Weintraub often bathed them in a rippling echo, making them sound as if they were being played back in a subway station.

Tico Records was about fancy, dressed-up Latin dance music, and the keyword was sophistication. Swing and Bebop influence was evident on nearly every recording date, and playbacks compared favorably to those of the best Jazz bands working at the time. It was major label quality with small label ambiance, and that's what probably drew so many great artists through the doors of its busy new offices at 220 West 42nd Street. It certainly wasn't Tico's royalty rate, which by most accounts was hardly competitive with that of the major labels.

Unfortunately, Goldner's spending habits had much to do with that fact! His passion for Latin music was dwarfed by his mania for gambling. He lost thousands of dollars on horse races and casino games, and his dependence on loans from Joe Kolsky grew. Soon, he was dealing directly with Kolsky's boss, Morris Levy, owner of the famed Birdland nightclub. Levy was widely believed to have gangland ties, and while Goldner was no pushover, he certainly must have been more than a little intimidated. When, in 1955, Levy was instrumental in getting Tito Puente signed to an album deal with RCA Victor, he could do little more than complain bitterly. By then, he was far too indebted to the club-owner to challenge his actions. On the other hand, Levy's seemingly inexhaustible sources of money gave Goldner the freedom to sign acts, record them and release product at a rate few other independent label owners could afford to. Accordingly, he took advantage of the situation and began to branch out.

Coming Soon . . .

Parts Three and Four

of the Tico Records Story

TITO RODRIGUEZ

.jpg)

Comments