Jeff Barry (Part Two)

THE JEFF BARRY STORY

by Hampton Jacobs

THE SHANGRI-LAS featuring MARY WEISS

The Leiber-Stoller Era

Around this same time, Leiber and Stoller were operating two fledgling labels, Tiger and Daisy Records. Barry and Greenwich contributed material to the labels' artists, and produced at least two Tiger/Daisy singles, "Big Bad World" by Cathy Saint and "I Won't Be Me Anymore" for teen idol Vic Donna. Then in early 1964, Lieber and Stoller joined forces with Rock 'n' Roll record mogul George Goldner to form Blue Cat Records and its sister label, Red-Bird. It was only natural that they should bring in their protégés, Jeff and Ellie, to write and produce for this new venture. In fact, they did more than that; they allowed the couple to become stockholders in the new company. Red-Bird ultimately proved to be the more successful of the two labels, due in large part to the talents of Barry and Greenwich. The pace was set when Red-Bird Records first release, The Dixie Cups' "Chapel Of Love" ensconced itself atop Billboard's Hot 100 list.

The Leiber-Stoller Era

Around this same time, Leiber and Stoller were operating two fledgling labels, Tiger and Daisy Records. Barry and Greenwich contributed material to the labels' artists, and produced at least two Tiger/Daisy singles, "Big Bad World" by Cathy Saint and "I Won't Be Me Anymore" for teen idol Vic Donna. Then in early 1964, Lieber and Stoller joined forces with Rock 'n' Roll record mogul George Goldner to form Blue Cat Records and its sister label, Red-Bird. It was only natural that they should bring in their protégés, Jeff and Ellie, to write and produce for this new venture. In fact, they did more than that; they allowed the couple to become stockholders in the new company. Red-Bird ultimately proved to be the more successful of the two labels, due in large part to the talents of Barry and Greenwich. The pace was set when Red-Bird Records first release, The Dixie Cups' "Chapel Of Love" ensconced itself atop Billboard's Hot 100 list.

BARBARA ANN HAWKINS

Of course, 1964 was the breakthrough year of the British Invasion, when The Beatles and other English Rock bands began knocking aside established American acts like so many tenpins in a bowling alley! The Brits had nothing on Barry and Greenwich, though; their uncredited production of "Chapel Of Love" muscled The Beatles' "Love Me Do" out of the #1 slot. In fact, 1964 was a banner year for the team: Between May and December, they produced 10 Red-Bird releases by The Dixie Cups, The Jellybeans, The Butterflys and The Shangri-Las, and every one landed on the national charts. Six of these made the Top Forty. Two were chart-toppers. Five months after The Dixie Cups' ode to nuptial bliss made the vaunted climb, lightning struck twice when Rock's first Punk girl group, The Shangri-Las, roared out of the box with their controversial classic "Leader Of The Pack". In addition to their Red-Bird hits, Barry and Greenwich charted two Raindrops singles in 1964 (three, if you count "Let's Go Together", which "bubbled under" the national list at #109), and scored an international best-seller with "Don't Ever Leave Me", a vigorous dance rocker they wrote and produced for Connie Francis (it made #42 Pop stateside). By now, people in the music business were really beginning to take notice of "Jukebox" Jeff. As a producer as well as a writer, he was clearly a force to contend with!

The Red-Bird/Blue Cat catalog is a treasure trove when it comes to the production work of Barry and Greenwich. There is much more of interest to the '60s Pop music collector than just familiar hits like The Dixie Cups' "People Say", The Shangri-Las' "Remember (Walkin' In The Sand)" and The Jellybeans' "I Wanna Love Him So Bad." Under Leiber and Stoller's supervision, Barry sharpened his production skills considerably; the records he created at Red-Bird convey a wide variety of musical influences. There's the fusion of New Orleans Rhythm 'n' Blues with New York Pop on The Dixie Cups' "You Should Have Seen The Way He Looked At Me"; the steady-rocking West Indian rhythms of The Jellybeans' "Baby, Be Mine"; the Motown-inspired grooves of Sidney Barnes' "I Hurt On The Other Side" and The Bouquets' "Welcome To My Heart"; the funky bump-and-grind of The Ad-Libs' "He Ain't No Angel"; and the stunning choral majesty of The Butterflys' "I Wonder" (an often-recorded but seldom heard tune from the Barry/Greenwich/Spector songbook).

The mini-epic "Train From Kansas City", hidden on the flipside of The Shangri-Las' seventh Red-Bird single, is arguably Barry's finest production from this period. Mary Weiss's impassioned lead singing is embellished by a gyrating rhythm track and dramatic steam engine whistles. If you think those authentic sounds were pulled from a sound effects disc, guess again! They were created vocally by "Jukebox" Jeff standing inside a studio echo chamber (as were the seagull noises heard on "Remember"). The song itself, concerning a young bride's rendez-vous with a former lover, is possibly the best Barry ever wrote with Greenwich. Many of their Red-Bird productions were done in collaboration with a third producer, usually Steve Venet, Joe Jones or George "Shadow" Morton. Leiber and Stoller would team their star protégés with newcomers who didn't have as much experience in the studio. Unfortunately, this could result in the new guy getting sole production credit on the record labels; it happened with Shadow Morton on "Give Him A Great Big Kiss" and several other Shangri-Las singles!

Of course, 1964 was the breakthrough year of the British Invasion, when The Beatles and other English Rock bands began knocking aside established American acts like so many tenpins in a bowling alley! The Brits had nothing on Barry and Greenwich, though; their uncredited production of "Chapel Of Love" muscled The Beatles' "Love Me Do" out of the #1 slot. In fact, 1964 was a banner year for the team: Between May and December, they produced 10 Red-Bird releases by The Dixie Cups, The Jellybeans, The Butterflys and The Shangri-Las, and every one landed on the national charts. Six of these made the Top Forty. Two were chart-toppers. Five months after The Dixie Cups' ode to nuptial bliss made the vaunted climb, lightning struck twice when Rock's first Punk girl group, The Shangri-Las, roared out of the box with their controversial classic "Leader Of The Pack". In addition to their Red-Bird hits, Barry and Greenwich charted two Raindrops singles in 1964 (three, if you count "Let's Go Together", which "bubbled under" the national list at #109), and scored an international best-seller with "Don't Ever Leave Me", a vigorous dance rocker they wrote and produced for Connie Francis (it made #42 Pop stateside). By now, people in the music business were really beginning to take notice of "Jukebox" Jeff. As a producer as well as a writer, he was clearly a force to contend with!

The Red-Bird/Blue Cat catalog is a treasure trove when it comes to the production work of Barry and Greenwich. There is much more of interest to the '60s Pop music collector than just familiar hits like The Dixie Cups' "People Say", The Shangri-Las' "Remember (Walkin' In The Sand)" and The Jellybeans' "I Wanna Love Him So Bad." Under Leiber and Stoller's supervision, Barry sharpened his production skills considerably; the records he created at Red-Bird convey a wide variety of musical influences. There's the fusion of New Orleans Rhythm 'n' Blues with New York Pop on The Dixie Cups' "You Should Have Seen The Way He Looked At Me"; the steady-rocking West Indian rhythms of The Jellybeans' "Baby, Be Mine"; the Motown-inspired grooves of Sidney Barnes' "I Hurt On The Other Side" and The Bouquets' "Welcome To My Heart"; the funky bump-and-grind of The Ad-Libs' "He Ain't No Angel"; and the stunning choral majesty of The Butterflys' "I Wonder" (an often-recorded but seldom heard tune from the Barry/Greenwich/Spector songbook).

The mini-epic "Train From Kansas City", hidden on the flipside of The Shangri-Las' seventh Red-Bird single, is arguably Barry's finest production from this period. Mary Weiss's impassioned lead singing is embellished by a gyrating rhythm track and dramatic steam engine whistles. If you think those authentic sounds were pulled from a sound effects disc, guess again! They were created vocally by "Jukebox" Jeff standing inside a studio echo chamber (as were the seagull noises heard on "Remember"). The song itself, concerning a young bride's rendez-vous with a former lover, is possibly the best Barry ever wrote with Greenwich. Many of their Red-Bird productions were done in collaboration with a third producer, usually Steve Venet, Joe Jones or George "Shadow" Morton. Leiber and Stoller would team their star protégés with newcomers who didn't have as much experience in the studio. Unfortunately, this could result in the new guy getting sole production credit on the record labels; it happened with Shadow Morton on "Give Him A Great Big Kiss" and several other Shangri-Las singles!

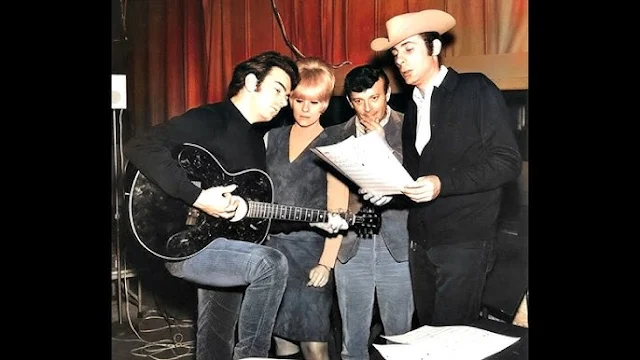

SHADOW MORTON

with ELLIE GREENWICH and JEFF BARRY

Some of the best Barry/Greenwich records on Blue Cat were cut with Sammy Hawkins, a Clyde McPhatter-styled Soul singer that George Goldner had brought to the company. Hawkins' first Blue Cat release was "Hold On, Baby", a steamy, Gospel-flavored number. It cracked the R & B Top Ten in the summer of 1965. The flipside, a tough Barry-Greenwich tune propelled by Bluesy piano chords, was called "Bad As They Come"; it anticipated the heavy Blues influences that surfaced later in Barry's work with The Archies ("Truck Driver"), The Monkees ("Oh, My My"), Bobby Bloom ("Careful Not To Break The Spell") and Neil Diamond ("Someday, Baby"). The follow-up single was a more Pop-oriented number, "I Know It's All Right". This record is literally built around the sterling harmonies of Hawkins and Greenwich; in truth, it's a duet. One-hundred-percent street corner Soul, guaranteed to please '50s vocal group enthusiasts! A playful reworking of Leiber and Stoller's 1958 Drifters hit "Drip Drop" titled "It Hurt So Bad" made for another interesting Sammy Hawkins flip.

with ELLIE GREENWICH and JEFF BARRY

Some of the best Barry/Greenwich records on Blue Cat were cut with Sammy Hawkins, a Clyde McPhatter-styled Soul singer that George Goldner had brought to the company. Hawkins' first Blue Cat release was "Hold On, Baby", a steamy, Gospel-flavored number. It cracked the R & B Top Ten in the summer of 1965. The flipside, a tough Barry-Greenwich tune propelled by Bluesy piano chords, was called "Bad As They Come"; it anticipated the heavy Blues influences that surfaced later in Barry's work with The Archies ("Truck Driver"), The Monkees ("Oh, My My"), Bobby Bloom ("Careful Not To Break The Spell") and Neil Diamond ("Someday, Baby"). The follow-up single was a more Pop-oriented number, "I Know It's All Right". This record is literally built around the sterling harmonies of Hawkins and Greenwich; in truth, it's a duet. One-hundred-percent street corner Soul, guaranteed to please '50s vocal group enthusiasts! A playful reworking of Leiber and Stoller's 1958 Drifters hit "Drip Drop" titled "It Hurt So Bad" made for another interesting Sammy Hawkins flip.

The third Sammy Hawkins single was slated to be "I'll Still Love You", a soulful handclapper that could easily have been a Tamla/Motown release. For some reason, Hawkins couldn't connect with the tune, so Barry cut it instead. A marked change of pace from his earlier Rockabilly sides, it's easily his best solo release of the '60s. Ellie Greenwich also waxed a solo single in '65; her entry was "You Don't Know," a dramatic, Adult-Contemporary ballad of unrequited love. Today, copies of it sell for hundreds of dollars on eBay, but at the time, it made zero commercial impact; neither did her husband's excellent platter, so the couple headed back to the studio with a new artist: Andrew Joachim, an ambitious young singer/songwriter from Canada. They recorded him as Andy Kim on a tune he co-wrote with them, "(I Hear You Say) I Love You, Baby". While there was no follow-up Andy Kim release, Barry liked the sound of Kim's singing voice and was determined to write with him again at some point. He couldn't have known at the time (or could he?) that within three years, Kim would succeed Ellie Greenwich as his songwriting partner.

ANDY KIM

The Barry/Greenwich express had slowed to a crawl by the middle of 1965. The team scored half as many charted productions as they had the previous year, and only two of these, "Iko Iko" by The Dixie Cups and The Shangri-Las' "Give Us Your Blessings" (originally a hit for Ray Peterson) made the Top Forty. The Girl Group trend, which had been the main vehicle for their work, was passing. The ongoing British Invasion had finally begun to take its toll. To complicate matters, the couple's marriage was on the rocks. Professional tension had spilled over into their personal lives, not an uncommon problem for married business partners; but an even bigger crisis was looming. A casual flirtation between Jeff Barry and Nancy Cal Cagno, the night manager of Mirasound Studios, had escalated into something more serious. In engineer Brooks Arthur's words, Cal Cagno "came between" Barry and Greenwich, hastening their estrangement. Before 1965 was out, Barry would ask his second wife for a divorce.

After their marital separation, Barry and Greenwich's professional relations understandably cooled as well. "We tried to write together after we split up, but it was awful", Greenwich recalled several years ago. "We couldn't . . . with divorce papers sitting right next to us." Reportedly, Phil Spector was responsible for salvaging the team. At his request, they reunited in early 1966 for the writing sessions that yielded Ike and Tina Turner's "River-Deep, Mountain-High" and The Ronettes' "I Can Hear Music" (the final Philles chart single, which Jeff Barry produced). After this project ended, Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich re-evaluated their creative partnership and realized it was still viable. They subsequently made the difficult decision to continue working together. However, their prospects were not as rosy as before. With more and more recording artists starting to write their own material, and new sounds being introduced onto the music scene, the changes in Rock 'n' Roll were coming fast and furious. Would the team be able to keep pace? Was there still a place for them on the charts?

The Gang At Bang

The answer to these questions came on 21 May, 1966, when a single called "Solitary Man" appeared on Billboard's Hot 100. The artist was Neil Diamond, and his name was destined to be a familiar one to record buyers for years to come. When Ellie Greenwich first encountered Diamond, he was just another down-on-his-luck songwriter; but both she and Barry thought there was something distinctly commercial about the brooding, introspective songs he wrote. They partnered with him in a new publishing company, Tallyrand Music, and then started shopping for a record deal.

First stop was Red-Bird Records, but much to their surprise, Leiber and Stoller showed little interest in Diamond. In fact, the two men were on the verge of selling their shares in the now-floundering label; on their advice, Barry and Greenwich would soon follow suit. Undeterred, Jeff Barry paid a visit to Atlantic Records' Jerry Wexler, and successfully sold him on Neil Diamond's talent. Wexler decided to place the handsome singer on Bang Records, a new Atlantic subsidiary run by writer/producer Bert Berns. Bang's Atlantic affiliation proved short-lived, as did Neil Diamond's time as a Bang artist, but both lasted long enough to launch his stellar recording career. At Bang, Barry and Greenwich began working with him in earnest, polishing their rough Diamond into a star. "Solitary Man" was the first of nine consecutive chart singles they would produce for him in 1966 and 1967.

With "Cherry, Cherry", Neil Diamond's second Bang single, the classic "Jukebox" Jeff sound was born. This record set the standard for Barry's late-60s productions. All the elements were there: The aggressive acoustic guitars, the crisp handclappings, the keyboard hooks, the south-of-the-border twist in Artie Butler's musical arrangement, and the Gospel-tinged, call-and-response backing vocals. This style of production stayed with Neil Diamond even after his association with Jeff Barry ended; you can hear echoes of "Cherry, Cherry" in his later hits for the Uni label like "Two-Bit Manchild", "Walk On Water" and "Crunchy Granola Suite". By now, Barry/Greenwich session regulars Artie Butler, Al Gorgoni, Russ Saunders and Gary Chester had been augmented by guitarists Hugh McCracken and Don Thomas, bass player Louie Mauro, pianist Stan Free, drummer Herbie Lovelle and percussionist Tommy Cerone from Neil Diamond's band. With Diamond himself contributing acoustic guitar licks, these men formed one wicked rhythm section!

Diamond was a Folk and Country-based songwriter, so the uncluttered backing tracks Barry and Greenwich created for him fit his tunes like a glove. Horns were used as coloring, and were never brassy. On "Kentucky Woman", the horn section is barely discernible. Strings (always a rarity for Jeff Barry productions) were used sparingly, usually to enhance a ballad like "Red, Red Wine" or "Girl, You'll Be A Woman Soon". Rather than falling back on a routine approach to production, Barry and Greenwich crafted each record to best showcase the singer and the song. Less was more! Barry has called "Solitary Man" his favorite Neil Diamond production, and his reason illustrates his basic musical philosophy. "It's a good example of not over-producing", he said, "(of) letting the song come through."

There's reason to believe that Barry's work with Diamond had a personal aspect to it. Prior to their association, Barry had been producing records mainly for groups of teenage girls with whom he had little in common. With Neil Diamond, he had an artist who was roughly the same age, and from a background similar to his own (both men are Brooklyn natives, as well as graduates of the same high school). Barry obviously identified more directly with Diamond, and some people believe this was reflected in the records they made together. Session horn player Artie Kaplan is one such person. Kaplan contracted the musicians for several early Neil Diamond sessions, and he observed firsthand the interaction between Barry and Diamond in the studio. "The inflections, the mannerisms, the phrasing in (Diamond's) records was really Jeff," Kaplan claims in the Neil Diamond biography Solitary Star. "If the name (on the singles) wasn't Neil Diamond, it might have been Jeff Barry". It's interesting to listen to records like "Shilo" and "Kentucky Woman" in this context and speculate on what might've been had Barry's own recording career not faltered.

The answer to these questions came on 21 May, 1966, when a single called "Solitary Man" appeared on Billboard's Hot 100. The artist was Neil Diamond, and his name was destined to be a familiar one to record buyers for years to come. When Ellie Greenwich first encountered Diamond, he was just another down-on-his-luck songwriter; but both she and Barry thought there was something distinctly commercial about the brooding, introspective songs he wrote. They partnered with him in a new publishing company, Tallyrand Music, and then started shopping for a record deal.

First stop was Red-Bird Records, but much to their surprise, Leiber and Stoller showed little interest in Diamond. In fact, the two men were on the verge of selling their shares in the now-floundering label; on their advice, Barry and Greenwich would soon follow suit. Undeterred, Jeff Barry paid a visit to Atlantic Records' Jerry Wexler, and successfully sold him on Neil Diamond's talent. Wexler decided to place the handsome singer on Bang Records, a new Atlantic subsidiary run by writer/producer Bert Berns. Bang's Atlantic affiliation proved short-lived, as did Neil Diamond's time as a Bang artist, but both lasted long enough to launch his stellar recording career. At Bang, Barry and Greenwich began working with him in earnest, polishing their rough Diamond into a star. "Solitary Man" was the first of nine consecutive chart singles they would produce for him in 1966 and 1967.

With "Cherry, Cherry", Neil Diamond's second Bang single, the classic "Jukebox" Jeff sound was born. This record set the standard for Barry's late-60s productions. All the elements were there: The aggressive acoustic guitars, the crisp handclappings, the keyboard hooks, the south-of-the-border twist in Artie Butler's musical arrangement, and the Gospel-tinged, call-and-response backing vocals. This style of production stayed with Neil Diamond even after his association with Jeff Barry ended; you can hear echoes of "Cherry, Cherry" in his later hits for the Uni label like "Two-Bit Manchild", "Walk On Water" and "Crunchy Granola Suite". By now, Barry/Greenwich session regulars Artie Butler, Al Gorgoni, Russ Saunders and Gary Chester had been augmented by guitarists Hugh McCracken and Don Thomas, bass player Louie Mauro, pianist Stan Free, drummer Herbie Lovelle and percussionist Tommy Cerone from Neil Diamond's band. With Diamond himself contributing acoustic guitar licks, these men formed one wicked rhythm section!

Diamond was a Folk and Country-based songwriter, so the uncluttered backing tracks Barry and Greenwich created for him fit his tunes like a glove. Horns were used as coloring, and were never brassy. On "Kentucky Woman", the horn section is barely discernible. Strings (always a rarity for Jeff Barry productions) were used sparingly, usually to enhance a ballad like "Red, Red Wine" or "Girl, You'll Be A Woman Soon". Rather than falling back on a routine approach to production, Barry and Greenwich crafted each record to best showcase the singer and the song. Less was more! Barry has called "Solitary Man" his favorite Neil Diamond production, and his reason illustrates his basic musical philosophy. "It's a good example of not over-producing", he said, "(of) letting the song come through."

There's reason to believe that Barry's work with Diamond had a personal aspect to it. Prior to their association, Barry had been producing records mainly for groups of teenage girls with whom he had little in common. With Neil Diamond, he had an artist who was roughly the same age, and from a background similar to his own (both men are Brooklyn natives, as well as graduates of the same high school). Barry obviously identified more directly with Diamond, and some people believe this was reflected in the records they made together. Session horn player Artie Kaplan is one such person. Kaplan contracted the musicians for several early Neil Diamond sessions, and he observed firsthand the interaction between Barry and Diamond in the studio. "The inflections, the mannerisms, the phrasing in (Diamond's) records was really Jeff," Kaplan claims in the Neil Diamond biography Solitary Star. "If the name (on the singles) wasn't Neil Diamond, it might have been Jeff Barry". It's interesting to listen to records like "Shilo" and "Kentucky Woman" in this context and speculate on what might've been had Barry's own recording career not faltered.

NEIL DIAMOND with ELLIE GREENWICH,

BERT BERNS and JEFF BARRY

One thing is known for sure: His work with Neil Diamond led directly to the next phase of his career, which was his association with "bubblegum" Rock groups during the late 1960s. The conduit to those groups was music publisher Don Kirshner, and Diamond was responsible for getting Barry and Kirshner together. As president of Screen Gems Television's music division, Kirshner was supervising music for a new NBC comedy series. "The Monkees" began as small screen spoof of Rock 'n' Roll bands, but the concept quickly escalated into a serious recording enterprise. "Last Train To Clarksville", the first single by the fictional band, had zoomed up the charts, and a national hysteria was building around the four actor/musicians who portrayed the group. Kirshner's ear for commercial songs was legendary in music business circles; during the late '50s and early '60s, he'd overseen the recordings of Neil Sedaka, Barry Mann, Tony Orlando, Little Eva and The Cookies. He loved the sound of "Cherry, Cherry" and Neil Diamond's other Bang hits, so he contacted the singer and solicited material for The Monkees. In the deal that ensued, Jeff Barry was tagged to produce any Diamond songs that the group would record.

When Barry and his session men entered RCA Victor's New York studios in October of 1966 to cut the tracks for "I'm A Believer", he'd never had a surer bet in his life. The Monkees may have been make-believe rockers, but nevertheless, they were the hottest up-and-coming act on the American music scene. Their second single already had advance orders in excess of one million, so it was guaranteed to be a Top Ten hit at the very least! Yet nothing could've prepared "Jukebox" Jeff for the monster "I'm A Believer" became upon its release the following month. The United States was only one of 16 countries where it topped the charts. Time hasn't diminished this record's appeal, either. "I'm A Believer" is one of the top 50 best-sellers of all-time! Its runaway success enhanced Barry's reputation as a producer tenfold, to say nothing for what it did for Neil Diamond's reputation as a songwriter (and for his bank account).

From the moment you hear its lively keyboard intro, it's clear that "I'm A Believer" could never have been anything but a major hit. Although Micky Dolenz's lead vocal was recorded separately from the instrumental track, the vocals and musical backing fit together as smoothly as cogs in a well-oiled machine. Barry's trademark handclappings and tambourine clashes make an ideal complement to the church revival meeting imagery in Diamond's lyrics. Dolenz is so caught up in the arrangement that he bursts out with a spontaneous cry of "I love it!" halfway through the song. Barry wisely kept this ad-lib on the final master; it enhances the record's good-time spirit. Monkees Davy Jones and Peter Tork are equally exuberant on background vocals, chanting the refrain with great fervor.

Davy Jones took the lead on the follow-up single, "A Little Bit Me, A Little Bit You". Barry energized this noticeably inferior Neil Diamond composition with tangy clavinet chords and forceful, prominent handclappings; this record's infectious rhythm simply cannot be escaped! While not as successful as "I'm A Believer" (alas, it peaked at a disappointing #2), "A Little Bit Me, A Little Bit You" was still tremendously popular upon its release in March of 1967, and it remains a favorite of Monkees fans. Davy Jones came into his own as a lead singer on this single. Other producers had pigeonholed him as a light Pop balladeer, but under "Jukebox" Jeff's direction, he proved that he could equal Micky Dolenz at belting out Rock 'n' Roll numbers.

Jones sang lead on most of the other Barry-produced tracks of this period, some of which appeared on the group's More Of The Monkees album ("Look Out! Here Comes Tomorrow", "Hold On, Girl", "The Day We Fall In Love", "Your Auntie Grizelda") and some of which have only recently become available ("Love To Love", "You Can't Tie A Mustang Down"). As it turned out, Barry cut more than just Neil Diamond tunes for Don Kirshner. After "I'm A Believer" exploded, Kirshner had him in the studio recording songs by Gerry Goffin and Carole King, Sandy Linzer and Denny Randell, Joey Levine and Artie Resnick, The Tokens and Jack Keller. Even three of Barry's own compositions, "Ninety-Nine Pounds", "She Hangs Out" and the aforementioned "Mustang", made it into The Monkees' repertoire.

BERT BERNS and JEFF BARRY

One thing is known for sure: His work with Neil Diamond led directly to the next phase of his career, which was his association with "bubblegum" Rock groups during the late 1960s. The conduit to those groups was music publisher Don Kirshner, and Diamond was responsible for getting Barry and Kirshner together. As president of Screen Gems Television's music division, Kirshner was supervising music for a new NBC comedy series. "The Monkees" began as small screen spoof of Rock 'n' Roll bands, but the concept quickly escalated into a serious recording enterprise. "Last Train To Clarksville", the first single by the fictional band, had zoomed up the charts, and a national hysteria was building around the four actor/musicians who portrayed the group. Kirshner's ear for commercial songs was legendary in music business circles; during the late '50s and early '60s, he'd overseen the recordings of Neil Sedaka, Barry Mann, Tony Orlando, Little Eva and The Cookies. He loved the sound of "Cherry, Cherry" and Neil Diamond's other Bang hits, so he contacted the singer and solicited material for The Monkees. In the deal that ensued, Jeff Barry was tagged to produce any Diamond songs that the group would record.

When Barry and his session men entered RCA Victor's New York studios in October of 1966 to cut the tracks for "I'm A Believer", he'd never had a surer bet in his life. The Monkees may have been make-believe rockers, but nevertheless, they were the hottest up-and-coming act on the American music scene. Their second single already had advance orders in excess of one million, so it was guaranteed to be a Top Ten hit at the very least! Yet nothing could've prepared "Jukebox" Jeff for the monster "I'm A Believer" became upon its release the following month. The United States was only one of 16 countries where it topped the charts. Time hasn't diminished this record's appeal, either. "I'm A Believer" is one of the top 50 best-sellers of all-time! Its runaway success enhanced Barry's reputation as a producer tenfold, to say nothing for what it did for Neil Diamond's reputation as a songwriter (and for his bank account).

From the moment you hear its lively keyboard intro, it's clear that "I'm A Believer" could never have been anything but a major hit. Although Micky Dolenz's lead vocal was recorded separately from the instrumental track, the vocals and musical backing fit together as smoothly as cogs in a well-oiled machine. Barry's trademark handclappings and tambourine clashes make an ideal complement to the church revival meeting imagery in Diamond's lyrics. Dolenz is so caught up in the arrangement that he bursts out with a spontaneous cry of "I love it!" halfway through the song. Barry wisely kept this ad-lib on the final master; it enhances the record's good-time spirit. Monkees Davy Jones and Peter Tork are equally exuberant on background vocals, chanting the refrain with great fervor.

Davy Jones took the lead on the follow-up single, "A Little Bit Me, A Little Bit You". Barry energized this noticeably inferior Neil Diamond composition with tangy clavinet chords and forceful, prominent handclappings; this record's infectious rhythm simply cannot be escaped! While not as successful as "I'm A Believer" (alas, it peaked at a disappointing #2), "A Little Bit Me, A Little Bit You" was still tremendously popular upon its release in March of 1967, and it remains a favorite of Monkees fans. Davy Jones came into his own as a lead singer on this single. Other producers had pigeonholed him as a light Pop balladeer, but under "Jukebox" Jeff's direction, he proved that he could equal Micky Dolenz at belting out Rock 'n' Roll numbers.

Jones sang lead on most of the other Barry-produced tracks of this period, some of which appeared on the group's More Of The Monkees album ("Look Out! Here Comes Tomorrow", "Hold On, Girl", "The Day We Fall In Love", "Your Auntie Grizelda") and some of which have only recently become available ("Love To Love", "You Can't Tie A Mustang Down"). As it turned out, Barry cut more than just Neil Diamond tunes for Don Kirshner. After "I'm A Believer" exploded, Kirshner had him in the studio recording songs by Gerry Goffin and Carole King, Sandy Linzer and Denny Randell, Joey Levine and Artie Resnick, The Tokens and Jack Keller. Even three of Barry's own compositions, "Ninety-Nine Pounds", "She Hangs Out" and the aforementioned "Mustang", made it into The Monkees' repertoire.

THE MONKEES featuring DAVY JONES

and MICKY DOLENZ

Barry's solo productions were everything a Barry/Greenwich production were, save one distinct difference: They were gutsier, had more of a Blues feel. Guitars were edgier, and the beat rocked harder! It was a totally masculine sound. Why Greenwich wasn't involved in The Monkees' recording sessions isn't clear, but this was hardly the only instance of Barry working without her in 1966 and '67. He was writing and producing singles for Gayle Haness, another Bang artist. In late '66, he and Bert Berns co-wrote and co-produced a McCoys chart entry, "I Got To Go Back (Watch That Little Girl Dance), and in May of '67, they teamed up again to produce the Top Thirty R & B hit "Am I Groovin' You" for Freddie Scott (Scott was signed to Bang's sister label Shout Records). The Drifters also benefited from the Berns and Barry magic: "I'll Take You Where The Music's Playing" (#51 Pop in 1965) and the fabulous Rock-a-Reggae floor-shaker "Aretha", a Northern Soul club smash in England. The finest of Jeff Barry's collaborations with Bert Berns are 1966's "Ride, Ride, Baby", a faux-live stomper sung by former Kingsmen lead singer Jack Ely and "Soul Motion", an incendiary 1967 Shout single released by The Exciters. In 1970, he'd help Berns' widow Ilene launch a new Bang Records artist named Paul Davis.

In addition to his work for Bang/Shout and Don Kirshner, Barry was producing sessions for Jay and The Americans and others, and he'd begun writing with Marty Sanders, Hank Shifter and Andy Kim. The sight of the tall, cowboy-hatted producer striding into a record date sans his bubbly blonde partner was becoming more and more common. He seemed determined to carve out a solo identity for himself and his work. His window of opportunity with The Monkees abruptly slammed shut in March of 1967 when the group had Don Kirshner dismissed as its music supervisor and subsequently chose Chip Douglas from The Turtles as its regular producer. Had these events not transpired, "Jukebox" Jeff would surely have claimed the latter job; but regardless, an important contact had been made.

Nineteen-sixty-seven was a pivotal year in Jeff Barry's career, and in his life. On January 23, he wed Nancy Cal Cagno. By mid-year, Leiber and Stoller's Trio Music had sold his publishing contract to Unart (United Artists) Music. This move allowed him to establish a tie with the West Coast movie industry and presaged the direction his career would take in the next decade. Around the same time, Barry decided to go to work for himself! He started up his own label, Steed Records, and cut a distribution deal with Randy Wood's Hollywood-based Dot Records. The Steed logo was a black stallion rearing up on its haunches, a reflection of Barry's equestrian interests. Andy Kim would be Steed's star recording act.

Finally, Bert Berns' death and Neil Diamond's defection from Bang Records, both occurring in December of 1967, precipitated the end of the Barry/Greenwich era. By now, Barry was commuting frequently to Los Angeles on business, and Greenwich opted not to duplicate his increasingly bi-coastal lifestyle. A 1968 Parrot Records single by The Down Five ("I'm Takin' It Home") is the last documented Barry/Greenwich co-production, but an October 1967 Atco single "Friday Kind Of Monday" b/w "Right Back Where I Started From" by The Meantime (a new incarnation of The Raindrops) is considered the team's official final outing. Yet, between singing numerous demo sessions, backing vocal dates and TV commercials, and running her own production company with new partner Mike Rashkow, Ellie Greenwich would find time to contribute harmony vocals to a number of Steed Records releases. For some people, the story ends here, but quite the contrary: some of "Jukebox" Jeff's biggest hits were yet to come! Nineteen-sixty-eight marked the beginning of an extremely busy four-year period for him. His work with another "bubblegum" band, The Archies, would account for much of that time.

.jpg)

Comments