Mad Hot Book Review #3

Chili Queens, Fajita Combos

and Margarita Madness!

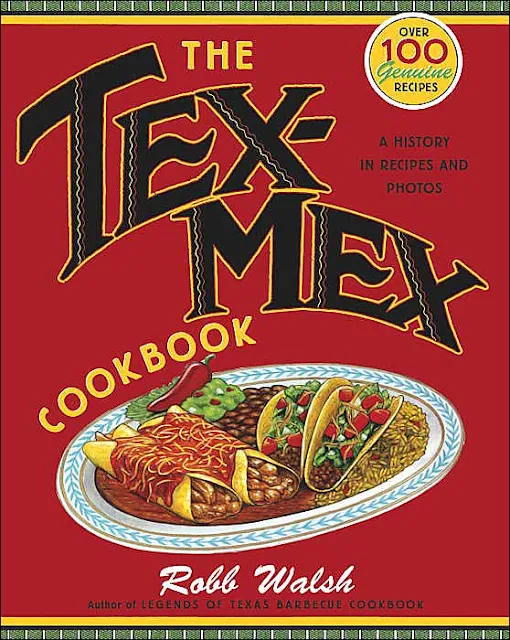

The Tex-Mex Cookbook

by Robb Walsh

The Tex-Mex Cookbook

by Robb Walsh

(Broadway Books, 2004)

reviewed by Hampton Jacobs

Is there anything quite so beautiful as a Tequila sunrise? What’s more satisfying to the soul than a savory bowl of chili con carne? Could the western world survive without tostadas, enchiladas and refried beans? And what kind of place would the Pop Culture Cantina be without Laura Pinto’s delectable shrimp tacos? Believe me, you don‘t even want to know! Around here, we hold Mexican food and drink in very high regard. Nothing goes better with retro pop culture! From time to time, my staff and I toy with the idea of transforming this joint into a full-fledged Mexican bar and restaurant. If we ever do, you can be sure that most of our recipes will come from un libro bien maravilloso called The Tex-Mex Cookbook. Published two years ago by Random House’s Broadway imprint, this remarkable resource was penned by Robb Walsh, a noted connoisseur of Texas food and culture. He serves up a tantalizing menu of tried-and-true specialties and fascinating historical narrative that’s guaranteed to tempt your palate and keep you coming back for more. ¿Te encanta la comida Mexicana? Do you adore Mexican dishes like Stuffed Animal does? Then Señor Walsh is just the caballero to teach you everything you ever wanted to know about the food he identifies as “America’s oldest regional cuisine.”

To be sure, his book is more than just a collection of recipes. It contains dozens of rare photos, vintage menus, original chili powder and picante sauce ads and transcribed oral histories from famous Tex-Mex restaurateurs and their descendants. Various Mexican-American dishes are listed and described in detail, along with an array of chili peppers (Ay yi yi! Watch out for those habaneras!) and kitchen equipment needed to create Tex-Mex cuisine, such as tortilla presses and bean mashers. Walsh covers all the expected topics in his chapters: Tamales, enchiladas, tacos, fajitas, Mexican desserts and chili. Naturally, the book includes numerous chili recipes, perhaps the most notable being one called “carne con chili.” This one’s a must for hombres like me who consider putting beans in chili a transgression akin to blasphemy! The venerable Mexican combination platter is honored with its own chapter, as is the ever-popular Margarita (unfortunately, my Cactus Daiquiri didn’t make the book, but it’s still a relatively new invention. . . give it time). There’s even a chapter devoted to Mexican “junk food,” which means you’ve got a handy recipe reference for suburban favorites like Tamale Pie, Frito Pie, Seven-Layer Bean Dip and Chili Mac! Be warned, though: Walsh’s recipes call for plenty of lard (which, he argues, isn’t really as bad for your health as you think).

The early history of Tex-Mex food is spun out in a series of vignettes set among old Spanish missions and cattle ranches. Researching the type of foods that were common among nineteenth century Anglo migrants to Texas, Walsh discovers a less-than-appetizing diet of “bacon, and cornbread, coffee sweetened with bee’s honey . . . butter, buttermilk and sometimes crackers.” Meanwhile, natives were chowing down on beef, venison, chicken, eggs, cheese, milk, sugar-sweetened tea and chocolate! “No wonder the Anglos became fond of Texas-Mexican food,” he wisecracks. Non-Hispanic Americans became fond of it as early as 1893, when Texas chili caused a sensation at the Chicago World’s Fair. Within a few years, tamale vendors had spread across the southern and Midwestern United States, most of them refugees from the bloody Mexican revolution of 1910-20. Right around this time, enterprising migrant women known as Chili Queens set up Mexican food stands in San Antonio’s Haymarket Plaza and began selling hot lunches to hungry cowboys. By the 1920s, the Chili Queens were doing brisk business. At one of their outdoor establishments, the uninitiated could sample the rudiments of what would become basic Mexican restaurant fare: Tacos, tamales, enchiladas, chile rellenos, frijoles, huevos rancheros (first called huevos revueltos) and, of course, chili con carne.

During the Great Depression, chili houses began to proliferate. They were literally lifesavers, providing thousands of down-on-their-luck Americans with inexpensive meals. By the late ‘30s, family-run Mexican restaurants were popping up all over the southwestern United States. Some catered to Latino migrants, but most drew a largely Anglo clientele. Robb Walsh uncovers early Mexican food menus that differ quite a bit from what you find today; alongside tacos and tamales, there frequently were North-American staples like spaghetti, scrambled eggs and bacon, and white bread! What’s more, picante sauces were toned down considerably for pepper-sensitive gringo palates. It took several more years before Mexican restaurants could fully live up to their name. That happened once the mixed plate caught on with the public. Invented by San Antonio’s Original Mexican Restaurant during the first World War, mixed plates (or combination platters) placed the emphasis squarely on indigenous foods. Dinners featuring Spanish rice, refried beans and grilled meats wrapped in fresh corn tortillas became widely popular by the 1940s. Was this food really indigenous to México, though? You certainly couldn’t buy a mixed plate in México City in 1942. Neither could you find dinners garnished with chili gravy, melted cheese and sour cream. No, this wasn’t indigenous Mexican food. It was something new, and gradually, it acquired the name “Tex-Mex.”

Mexican-American cooks created a distinctive regional cuisine which drew from traditional Mexican foods but took advantage of ingredients that were more readily available north of the border, like inexpensive cuts of beef. Unlike México’s haute cuisine which was based on continental European dishes, Tex-Mex reflected the tastes of working class Anglos and Latinos. What was called “Mexican food” in the United States ended up being far more American than Mexican in character. Food critics blasted Tex-Mex cooking as inauthentic, but most Americans couldn’t have cared less. They were too busy enjoying their burrito spreads! Robb Walsh sums up their attitude quite nicely, concluding that “authenticity is highly overrated.” Tex-Mex cuisine thrived during the '40s and ’50s, but in the 1960s, Americans of all ethnicities were seduced away from it by McDonald's and other fast food franchises. Mixed plates began falling out of favor and came perilously close to becoming chili-and-cheese-covered relics of the past. Happily, the advent of fajita combos and frozen Margaritas in the early ’70s revitalized Mexican restaurants and brought people flocking back to them. Current south-of-the-border crazes like fish tacos, Mexican pizza, meat nachos and monster burritos are a sure sign that America’s Tex-Mex tradition is still going strong. The Tex-Mex Cookbook documents its century-spanning journey from border town greasy spoons to chic European bistros. Along the way, it commemorates such legendary Mexican eateries as the original Casa Río Restaurant, the Old Borunda Café, El Matamoros, Molina’s Restaurant, the Texas Grill, Henry’s Puffy Tacos, the Chuy’s franchise, the Loma Linda, El Fenix and El Chico chains, and the original Cadillac Bar.

Learn how to make delectable Mexican dishes like Ox Eyes (eggs fried in oil), Barbacoa (cow’s head), Lengua (beef tongue), Fried Oyster Nachos and Café de Olla (coffee with unfiltered grounds)! Learn why Velveeta and Rotel are not necessarily bad words. Discover the real difference between “authentic” Mexican food and Tex-Mex (and why your authentic Mexican menu had better have chips and salsa on it if you want to stay in business)! Read about Carolina Borunda, the Depression-era restaurant owner who beat rowdy patrons over their heads with her bean masher; Big Rikki, the Guacamole Queen of Austin, Texas, who catered to a rock star clientele; Houston’s beloved Mama Ninfa, who popularized the fajita combo platter; Nacho Anaya, inventor of everyone’s favorite football game snack, the nacho; baseball game mascot Wes Ratliff, who regularly risks life and limb by appearing in public dressed as a Puffy Taco; Mariano Martinez, the hombre who’s most to blame for Margarita madness; and Mexican-American restaurant king Felix Tijerina, the very embodiment of Chicano pride and upward mobility. Have a seat at the outdoor dinner table of a turn-of-the-century Chili Queen, sample Mexican dishes the way they’re prepared in Paris, France, and learn the truth behind the rise and fall of the Frito Bandito. You can find it all inside this invaluable reference book.

.jpg)

Comments