Habanera Rock, Part One

The 1960s Habanera Rock Revolution

by Hampton Jacobs

Baby, you're a genius when it comes to

cookin' up some chili sauce . . .

cookin' up some chili sauce . . .

Excerpt from "You're The Boss" by

Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller,

copyright 1961 Sony/ATV Songs LLC(BMI)

copyright 1961 Sony/ATV Songs LLC(BMI)

It's Ben E. King weaving a romantic spell around "Spanish Harlem" . . . Soul music pioneer Clyde McPhatter going plumb Latin "Deep In The Heart Of Harlem" . . . Marvin Gaye inviting you to dance the cha-cha-chá with that "Stubborn Kinda Fella" . . . Len Barry dressing up the Latin boogaloo in Motown trappings on "One-Two-Three" . . . The Reflections making like a flamenco troupe on "Just Like Romeo and Juliet" . . . Curtis Mayfield adapting Brazilian rhythms for the urban dance floor on Major Lance's "The Monkey Time" and "Um, Um, Um, Um, Um, Um" . . . Joe South slapping a Tex Mex tango arrangement onto Billy Joe Royal's "Down In The Boondocks" . . . Gene Pitney crossing the bossa nova with mariachi horns on "Last Chance To Turn Around" . . . . Elvis Presley rocking the samba in his films Fun In Acapulco and Viva Las Vegas . . . and Diana Ross + The Supremes putting on Spanish airs with "Ask Any Girl."

When musicians called it anything at all, they referred to it as "Jewish Latin," but a more accurate title for the sound is Habanera Rock. It's a potent Pop/Rock/Soul sound from the 1960s that found Cuban, Brazilian, Spanish and Mexican rhythms at the foundation of hits like Steve Alaimo's "Every Day I Have To Cry," Tony Orlando's "Bless You," Neil Diamond's "Cherry, Cherry," Gene McDaniels' "Spanish Lace" and Gary US Bonds' "New Orleans." A highly commercial sound, it raked in huge profits for the North American music industry until the advent of The Beatles and other British Invasion groups (whose early recordings were influenced by it).

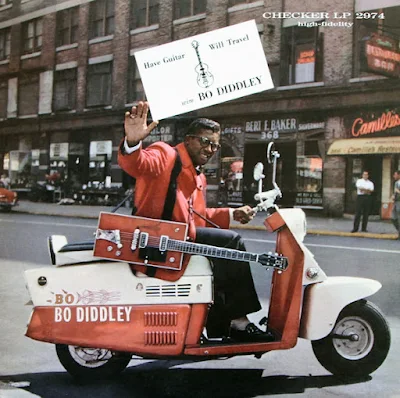

There were precedents for this trend in the previous decade: The music of Bo Diddley, and hit records like The Diamonds' "Little Darlin'", Buddy Holly's "Not Fade Away", Ray Charles' "Mary Ann" and Johnny Otis's "Willie and The Hand Jive." It was producers Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller who really kicked the trend into overdrive with their groundbreaking 1959 production of "There Goes My Baby" for The Drifters. With The Drifters, their former lead singer Ben E. King, and Jay + The Americans (another Leiber and Stoller-produced group) anchoring the Habanera Rock movement, it spread across the airwaves and into A & R departments all over the country . . . in Nashville, Detroit, Chicago, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and even beyond American shores.

Records by artists as diverse as Ral Donner, Johnny Nash, Billy J. Kramer and The Dakotas, Chubby Checker and Eydie Gormé held forth with this sound, and Girl Group records galore (influenced by Phil Spector's productions for Darlene Love, The Crystals and The Ronettes) were resplendent with castanets and habanera rhythms. It was a wonderful red, white and blue sound (red for Latin backbeats; white for classically-influenced melodies; and blue for Country/Gospel-based vocal arrangements) that was popularized by a group of East Coast songwriters and producers. Here at the Pop Culture Cantina, we use "Habanera Rock" as a blanket term to talk about any Rock 'n' Roll music produced during the 1950s and '60s that has a Latin rhythm foundation. However, this essay focuses mostly on the kind that came out of New York City in the early '60s.

The habanera itself is a four-beat rhythm pattern that was born in the barrios of Havana, Cuba during the 19th century. From its island birthplace, it spread throughout Latin America and became particularly popular in Argentina and México. An 1859 habanera song called "La Paloma," composed in Cuba four years earlier by Spanish composer Sébastian Yradier, was a huge hit with the Mexican public. It later sold reams of sheet music in the United States and is believed to be the first Latin composition to achieve hit status in North America. Habaneras next invaded our shores by way of Argentina during the 1910s, when the tango craze was in full blossom. Its four-beat structure lay at the base of the tricky, twisting dance step that earned stardom for Rudolph Valentino when he performed it in the 1921 box office smash The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. WC Handy's famous 1914 composition "St. Louis Blues" is a tango, though often mistaken for a Blues number, and its inclusion in the repertoires of Jazz bands helped embed the habanera rhythm in the public's subconscious mind.

Tango gave way to rhumba in the 1930s, which in turn gave way to mambo in the 1940s and cha-cha-chá in the '50s. All of these dance music styles were Cuban in origin, but the newer ones featured a clave rhythm that differed from the habanera. Even so, the tango beat remained in the North American musical lexicon, especially in Jazz circles. The habanera's close similarity to the three-beat baião, which Leiber and Stoller borrowed from Brazilian music for Pop recording dates, facilitated its re-emergence during the Rock Era.

In fact, many of the so-called baião beats Rock critics refer to when they talk about '60s music are actually habaneras (listen for that fourth beat)! Why the confusion? Well, a fair number of the studio musicians who appeared on early Rock 'n' Roll records were Jazz players. The familiar old Cuban rhythm from "St. Louis Blues" probably came more naturally to them than the newer Brazilian one. Leiber and Stoller called it one thing, and musicians may have mistaken it for something else, but whatever communication mix-ups there were, it didn't affect the quality of the music at all.

Songwriters affiliated with Peer International and EB Marks Music were largely responsible for spreading Latin music inside US borders during the 1930s and '40s. Tunesmiths contracted to certain publishing companies in the 1960s performed the same function for Habanera Rock. Most were Jewish, and several plied their trade in Manhattan's Brill Building. There were those who worked under Leiber and Stoller at Trio Music, including Jeff Barry, Ellie Greenwich, George "Shadow" Morton and Tony Powers. There were songwriters like Doc Pomus, Mort Shuman, Pete Anders and Vini Poncia, who wrote for Hill and Range Music. There were the writers contracted to Bob Crewe's Saturday Music firm, including Bob Gaudio, Gary Knight, Sandy Linzer, Denny Randell and Crewe himself. Also important were TM Music songwriters like Kenny Young, Artie Resnick and Rudy Clark.

Most important of all were the large stable of writers who worked for Al Nevins and Don Kirshner's Aldon Music (later Screen Gems Music Division): Gerry Goffin, Carole King, Barry Mann, Cynthia Weil, Neil Sedaka, Howie Greenfield, Jack Keller, Toni Wine, Artie Kornfeld, Roger Atkins, Helen Miller, Russ Titelman and others. Rounding out this influential group were independent and freelance writer/producers like Ben Raleigh, Mark Barkan, Bert Berns, Neil Diamond, Burt Bacharach, Jerry Ragovoy, Johnny Madara, Dave White, Hank Medress and the members of The Tokens, the team of Bob Feldman, Jerry Goldstein and Richard Gotteher, and Phil Spector.

Most of these composers merely used Latin rhythms as flavorings in their music, nothing more. The fact that one composition might be a samba and another might be a waltz wasn't particularly significant to them. However, a handful were avid Latin music enthusiasts. When Bert Berns, Mort Shuman, Neil Sedaka, Burt Bacharach or Mike Stoller wrote Latin backbeats into their songs, they did so as men with an agenda. They mixed Latin, Classical and Blues/Gospel elements toward the end of creating a new dynamic. Create it they did, dynamic it was, and finely crafted records like Sedaka's "Oh! Carol" and "King Of Clowns," Shuman's "Sweets For My Sweet" and "Save The Last Dance For Me," Berns' "Twist and Shout" and "Hang On, Sloopy, " Stoller's "Down In México" and "Three Cool Cats" (which predate The Drifters' Latin excursions) and Bacharach's "Reach Out For Me" and "Twenty-Four Hours From Tulsa" pointed the way for everyone else.

Bacharach's music became so closely linked to the Brazilian bossa nova that at one point, Dionne Warwick is said to have believed he invented the rhythm! Bert Berns was very partial to Mexican music, although the Latin boogaloo (derived from the Cuban cha-cha-chá) seems to have been his rhythm of choice for writing. A casual listen to Phil Spector's output between 1963 and 1966 reveals an obvious affinity for the Spanish pasodoble; its inherent dramatic flourishes certainly worked to the advantage of his "Wall of Sound" production style. Examine the rhythm patterns of early Motown releases, and it becomes clear that somebody in Hitsville USA's A & R department was enamored of the cha-cha-chá. In fact, cha-cha backbeats (no doubt inspired by The Champs' beloved 1958 hit single "Tequila") are almost as rampant in '60s Rock 'n' Roll records as the word "baby!" One of the most famous examples is Roy Orbison's 1964 smash "Oh! Pretty Woman."

Musical arrangers were on hand to translate these fusion sounds to studio musicians, and given that some of the aforementioned writer/producers didn't have formal music training, their contributions were absolutely essential. The best Habanera Rock records cut in New York City and Hollywood had names like Artie Butler, Alan Lorber, Charlie Calello, Bert Keyes, Teacho Wiltshire, Jack Nitzsche, Perry Botkin, Jr, Ernie Freeman, Klaus Ogermann, Jimmy "Wiz" Wisner, Chuck Sagle and (especially) Gary Sherman and Stan Applebaum emblazoned on their labels. Nashville product invariably featured arrangements by Bill McElhiney, Bill Justis, Don Tweedy, Bob Moore or Ray Stevens (yes, that Ray Stevens). In Chicago, Johnny Pate was the man to go to when you needed a little Spanish Fly. Some of these arrangers made their mark as songwriters, too. They were the best in the business, and they wrote charts for everybody, be it Top Forty mainstays like Connie Francis, Brenda Lee and Bobby Vee or relatively obscure artists like Vic Donna, Lou Johnson or Babs Tino. Individually and collectively, they brought a little chili seasoning along with them to every recording session. However, certain artists became more closely associated with Habanera Rock than others.

.jpg)

Comments